“It is an insult to a nation to tell us that hijab is our culture, that gender segregation and misogyny is our culture.” – Masih Alinejad.

The death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini gave birth to protests in Iran. Women removed their headscarves in protest at the compulsory wearing of hijabs. The government curtailed internet and social media access and deployed security forces in response. Countless protestors have been detained, injured, and killed.

This week, the United States imposed sanctions against the morality police and seven other senior Iranian leaders “for abuse and violence against Iranian women and the violation of the rights of peaceful Iranian protestors.”

Mahsa is the latest victim. Aqsa Parvaz, a sixteen-year-old girl in Ontario, Canada, was strangled to death by her father and brother over the hijab.

In Texas, Amina and Sarah Said were shot and killed by their father, and in the United Kingdom, Banaz Mahmod was killed by her family, chopped up and stuffed into a suitcase and buried in her family’s backyard.

The headscarf has been used for political, religious and practical purposes for centuries, serving either conservative or rebellious purposes. It has remained at the centre of debates about women’s rights, identity, power and class.

The hijab has a long history. This type of head covering has been in existence long before Islam came into being and is even also worn by women from a variety of religious traditions.

Verse 59 of Surah Al-Ahzab, states, “O Prophet, tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to bring down over themselves of their outer garments. That is more suitable that they will be recognised and not be abused. And ever is Allah forgiving and merciful.”

Head coverings were first written into law around the 13th Century BC, in an ancient Assyrian text that mandated that women, daughters and widows cover their heads as a sign of purity.

Those women who were family to “seigniors” had to veil, and women who had previously been prostitutes but were now married. Laws on veiling were so strict that intolerable consequences were enacted for these women, some of which included being severely beaten or cutting their ears off.

Prostitutes and enslaved people were prohibited from veiling. The veil was not only used to classify women according to their status, but it also labelled them based on their sexual activity and marital status.

Women’s rights in Iran were severely restricted in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries compared to most developed countries. Iran was ranked 140th out of 144 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Global Gender Gap Report.

Islamic history records a tremendous level of oppression of women before the coming of Islam to the Middle Eastern areas, especially in Arabia. The strict enforcement of the wearing of veils and hijabs and female infanticide are common denominators of the era.

This period is known as the Jahiliyya period, the era of ignorance. This is because information on women in pre-Islamic Arabia is scarce. The majority of it is derived from historical narratives and hadith, ancient poetry, early biographies, or interpretations of verses from the Qur’an.

The jahiliyyah period might be considered the worst period of women’s rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and possibly other regions of Africa that came in contact with and imitated Arabian culture.

Contrary to what many stereotypes depict. Islamic fundamentalism isn’t the worst form of oppression women have faced. From the records and the evaluation of the doctrines of Islam, we can deduce that Islam was a feminist movement that empowered women and gave them explicit rights and equal opportunities in this ruthless society.

A clamour for Islamic fundamentalism and extremist views became widespread in the late 20th century. At its core is the belief that Islamic states should return to the systems of government used during the time of the Prophet, as well as implement certain assumptions. The problem with Islam fundamentalism is how easily it became radicalised.

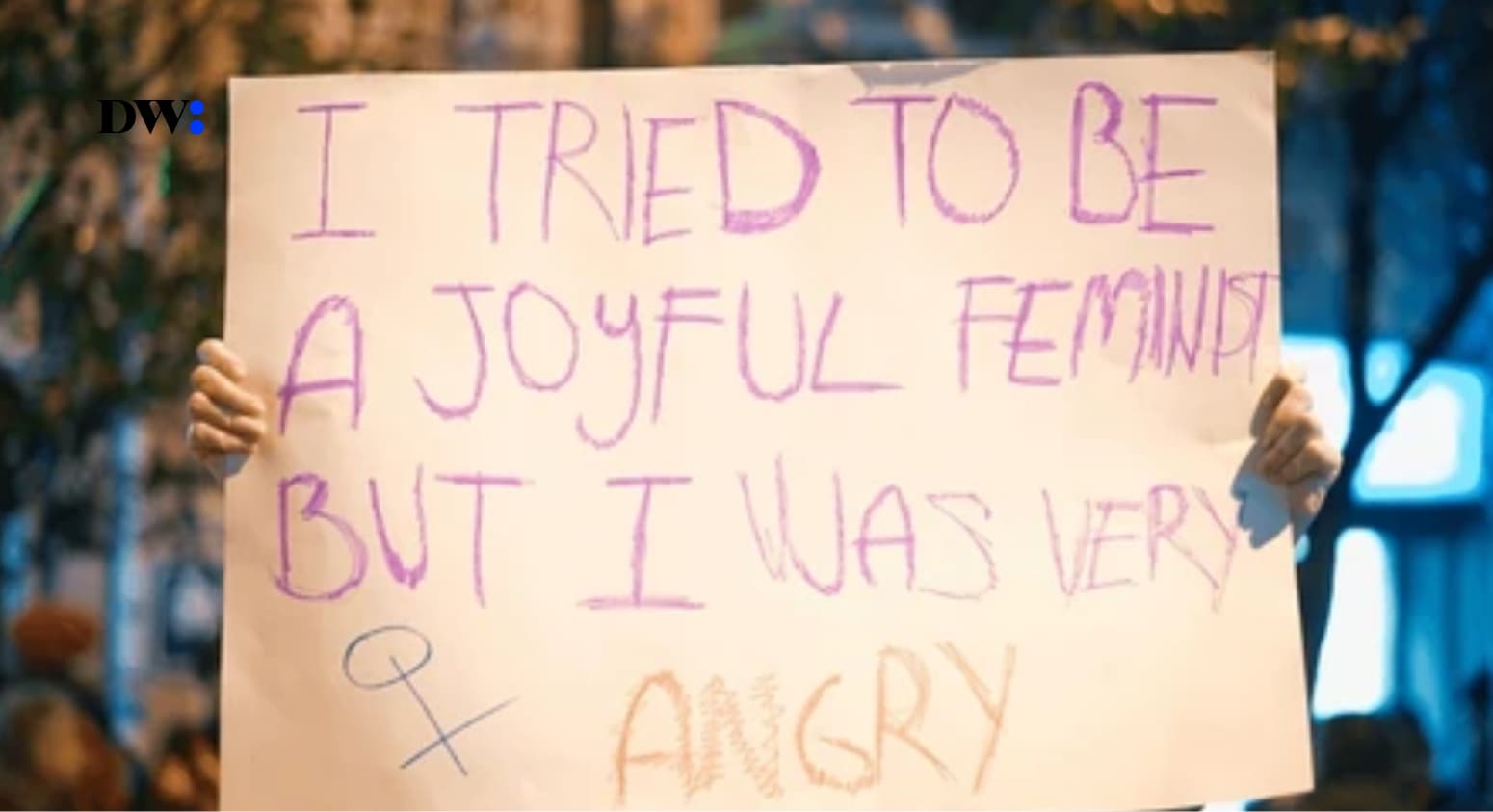

In a previous article about the hijab, I asked, “Why does the hijab have to be associated with violence?” I guess the death of Mahsa Amini answers that.

These oppressive laws and policies are a product of a solid impulse to control and police women’s bodies more often than not. It is not about the hijab itself but the concept of not allowing women the freedom to do whatever they choose to do with their bodies.