On 18 November 1929, the Aba Women riot/rebellion began, the movement among Nigeria’s Aba women was notably the first major challenge to British authority in Nigeria and West Africa during the colonial period.

Sixteen native administration facilities were attacked, with the majority of their native Courts being torn up or torched. Over 50 women were murdered in open fire during the two-month “war” that saw over 10,000 women from primarily six ethnic groups—Ibibio, Andoni, Orgoni, Bonny, Opobo, and Igbo—rise against economic and socio-political oppressions in Bende, Umuahia, and other districts of Igboland.

However, as is well known, the Aba women’s riot was not an isolated incident but rather the culmination of months of mounting tension. Still, what might have prompted over 10,000 ladies to violate the colonial orders of a district officer?

Here’s one history class you might have missed out on…

The indirect rule system in Igboland, lacking a unified political institution, a significant disparity between ruling in the South and North, involved the appointment of warrant chiefs by Lord Lugard. Although they weren’t universally respected, these warrant chiefs were the de facto emblem of authority, which gave rise to oppressive legislation.

It so happened that in 1929, Captain J. Cook, an assistant District Officer, was sent to take over the Bende division temporarily from the serving district officer, and as a result of his re-evaluation of the nominal tax rolls, the direct taxation on men (introduced in 1928 without major incidents, thanks to the careful propaganda) was revised to now include information about the number of wives, children, and livestock in each household. This meant that the recently implemented taxes on men would be extended to women.

How receptive could the women have been to this?

The unexpected took root in Oloko town when the warrant chief, Okugo, sent a representative on 18 November 1929 to conduct the census for the tax, which took him to the home of a widow named Nwanyereuwa. Having instructed her to count her live stocks (which meant she would be taxed based on the number of livestock), the widow flared, and a fight ensued when Nwanyereuwa asked, “Was your mother counted?”

With fire brewing in her, she took the matter to the town square to find other women who happened to be deliberating on the tax issue. Her account, backed by the pains of falling palm-produce prices and new customs duties which had put up the cost of several imported articles of daily use, prompted the women to call for a meeting (using palm leaves from other areas of the Bende district, signifying a call for help), after which they conclude there was a need to “sit on the men”.

Using the customary technique of censoring boys and men via all-night singing and dance humiliation (called “sitting on a man”), the women sang and danced, and several warrant chiefs resigned. At Utu-Etim-Ekpo, hordes of barely clothed women with charcoal-smeared faces, palm-wreathed poles, and fern-bound heads emerged. The women targeted European retailers and Barclays Bank and stormed into jails to free inmates. They burned numerous colonial-run Native Courts.

Thereafter, the police and soldiers were dispatched, and on two separate instances, when the women raced toward them shouting hysterically, the soldiers opened fire with rifles and a Lewis gun on December 17th, resulting in the deaths of more than 50 women in Calabar and Owerri.

Roughly 10,000 women showed up for a demonstration that demanded the warrant chief be fired and put on trial. Aba women’s riot had such an impact on the British government that they abandoned plans to tax market women, and took steps to limit the authority of the warrant chiefs, both of which would go down in history as a direct consequence. Furthermore, women’s rights were advanced when they were appointed to the post of chief warrant in various regions.

The women’s rebellion is often seen as the first significant threat to British dominance in colonial Nigeria and West Africa. Sixteen Native Administration buildings were vandalized, and the vast majority of Native Courts were destroyed. At least 10,000 Igbo women demonstrated against British authorities during the two-month “war.”

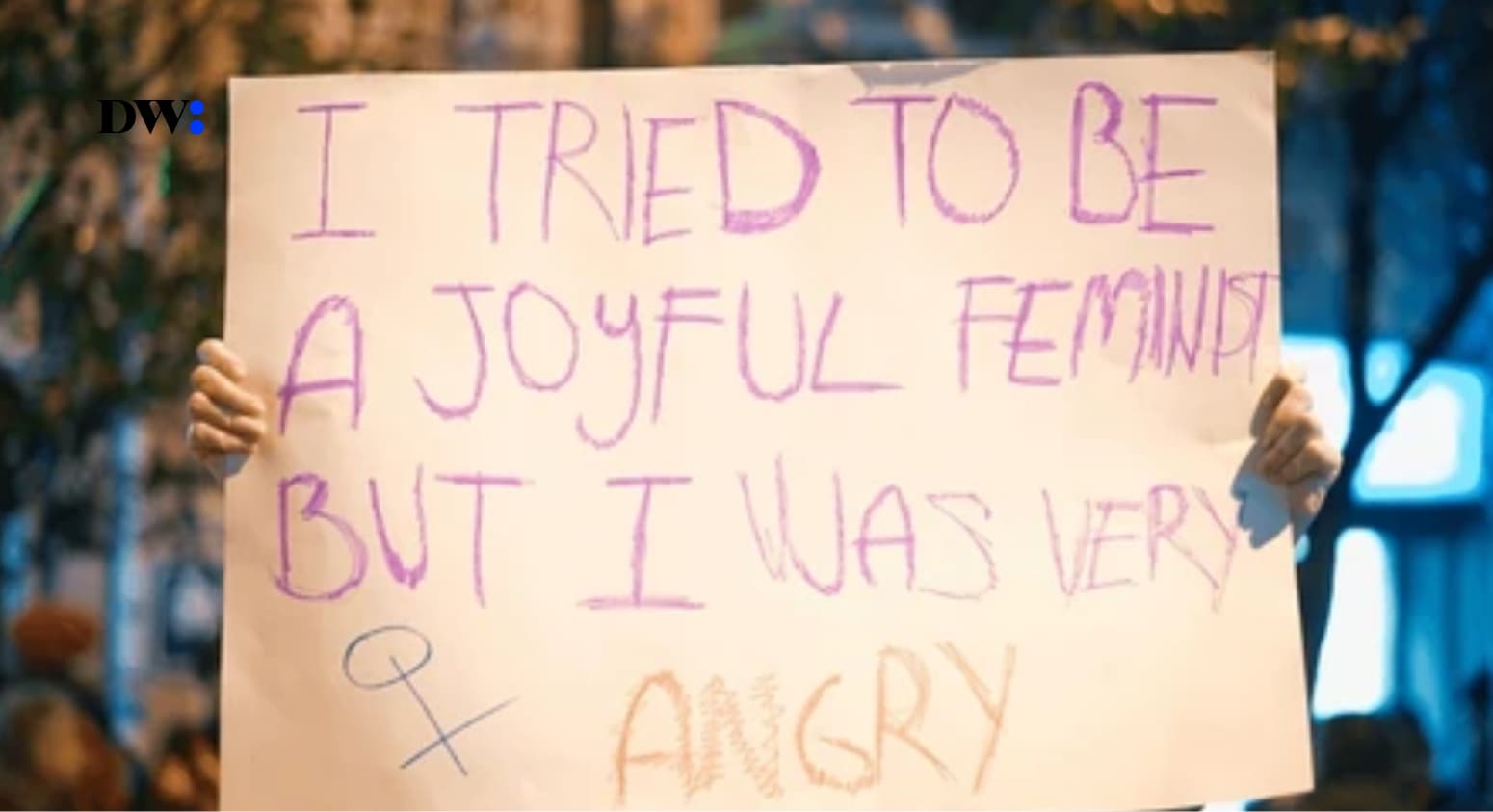

The Aba women are not the only ones fighting for change. Lots of women in contemporary societies who have shown incredible resilience, are taking the lead and joining the fight against oppression on all fronts; disease, climate change, security, etc. These women are the backbone of their communities, as mothers, carers, humanitarian workers, health workers, leaders, advocates, volunteers, bread winners, etc.

On International Women’s Day 2021, Feed the Minds singled out some heroines with the above qualities and honoured them accordingly.

Some of them are;

- Zahra Abdi, in Tanzania, who adapted her service to reach more survivors of gender-based violence

- Mercy Anjela, in India, who supported people who are living in poverty,

- Loice Barayona, in South Sudan, who volunteers to support pregnant women in her community while growing food for her family and community.

- Rita Bill, in Vanuatu, who helped relieve economic stress caused by Covid-19 in local communities.

- Mbambu Bridget, in Uganda, who has been making soap for Covid-19 prevention in her community and teaching others how to make soap too.

- Sarah Dawa Eluzai, in South Sudan, who distributed emergency food packages to women and people living with disabilities in remote villages.

- Ilunga Guerschom, in Malawi, who made face masks for fellow refugees in Dzaleka refugee camp.

- Walumatu A. Kamara, in Sierra Leone, who helped her community continue to farm and sell produce safely in the pandemic.

- Margaret Kamanda, in Sierra Leone, who shared her food with others and promoted Covid-19 prevention measures.

- Tripti Khatun, in Bangladesh, who supported her family while also making and distributing face masks and teaching good hygiene in her community.

- Biira Margret, in Uganda, who raised awareness of menstrual health and distributed sanitary pads to displaced women and girls, Rachel Samson Millinde, in Tanzania, who provided training in farming and also gave her home grown produce to women who couldn’t work.

- Dhanalakshmi Pandiarajan, in India, who supported families living in poverty through providing literacy training.

- Diana Sesay, in Sierra Leone, who distributed masks and supported families through buying goods if they couldn’t reach shops, and

- Adama B. Sesay, in Sierra Leone, who raised awareness of Covid-19, while advocating for women’s rights.

Our faith in a more just and equitable society, has been renewed by the presence of such powerful and motivating women as well as many others, at the forefront of the movement for change.