“To the people on the island, a disappeared thing no longer has meaning. It can be burned in the garden, thrown in the river or handed over to the Memory Police. Soon enough, the island forgets it ever existed.”

The power of memory takes centre stage in this brilliant speculative fiction novel woven in seamless allegory, a veiled reminder of the political and sociological forces that have been and will always try to take away meaningful rights in ways we do not notice until they are gone, a lesson on disrupting the callous powers of such authority.

Yōko Ogawa has won every major Japanese literature award, and The Memory Police, initially published in Japan in 1994 but now translated excellently into English, reaffirms her place as one of her generation’s most influential Japanese writers.

“In those days, everyone could smell perfume. Everyone knew how wonderful it was. But no more. It’s not sold anywhere, and no one wants it. It was disappeared the autumn of the year that your father and I were married. We gathered on the banks of the river with our perfume. Then we opened the bottles and poured out their contents, watching the perfume dissolve in the water like some worthless liquid.”

Many have described the story’s premise as “Orwellian”, as it immediately comes off as a descendant of the dystopia of George Orwell’s “1984.”

Still, The Memory Police takes on its own life and offers up a riveting tale set on an unnamed island where objects are constantly “disappeared” physically and from the minds and memories of the island’s inhabitants. The people on the island who hold onto items that have disappeared know the danger they court, and those who can somehow remember those items are in peril.

The Memory Police, in their sleek and elegant uniforms, keep everyone in line. People who remember are carted away in green vans, never to return.

Our unnamed protagonist is a young novelist. Her mother was a sculptor and a hoarder of banned items. Her father was an ornithologist, an expert on birds, birds soon to be disappeared. She only has two friends: her publisher/editor and an old family friend who ran the ferry boat to the mainland before the ferry itself “disappeared.” She does not remember the disappeared things.

Yōko Ogawa offers no explanation for either the mechanism or the rules of disappearing. Disappearing, written with gentle and simple prose, is used to explore the role of memory in personality, as individuals and as communities – Losing memories changes people. Are the people on the island worse for not remembering?

We begin with our protagonist as a calm, somewhat easygoing person who isn’t determined to defy the system, even after losing her mother to the memory police as a child. As the story progresses, things we cannot imagine living without are disappeared: birds, roses, fruits…

These disappearances and the exploration of what we do afterwards make this a book about loss. Loss permeates The Memory Police, from the loss of both the heroine’s parents to the disappearance of things the inhabitants of the island hold dear and the implications; the old man loses his livelihood when ferries are banned. The people of the island pour perfumes into the sea and fill their waterways with roses that lose meaning as the reds and violets flow away. Our protagonist writes her newest story, on how a girl lost her voice, and the sorrow rings through. Loss is a facet of life, but how much is too much loss?

The protagonist sometimes wonders about their existence- sometimes, they remain tangible but meaningless to the island. Her mother’s emeralds may as well be another rock. Her worldviews are tested by her editor’s recollection of disappeared things. To protect him from the Memory Police, she hides him. In remembering, R is a guardian of both collective and personal memory, just like her mother. Writing is a means of preserving history and the understanding of what it is to be human, and a writer who remembers is everything. If he is taken by the memory police, the island is lost.

As certain objects in the community’s collective understanding evaporate, each loss less impactful than the one before, the biggest losses still linger on the horizon.

“My memories don’t feel as though they’ve been pulled up by the root. Even if they fade, something remains. Like tiny seeds that might germinate again if the rain falls. And even if a memory disappears completely, the heart retains something. A slight tremor or pain, some bit of joy, a tear.”

The Memory Police reads like a nightmare unfurling. The Memory Police, a sinister organisation tasked with enforcing the disappearance of objects by seizing them and policing the population, are a mirror to the constant use or misuse of enforcement agencies by governments- they spew propaganda to justify heinous crimes and the people sigh and groan, but the people go.

The setting and characters are provided with just enough detail that, for each reader, the world draws on their fear and is different. A reflection on what we must remember in the face of the mass repression by the state; readers all over the world can find themselves in this book.

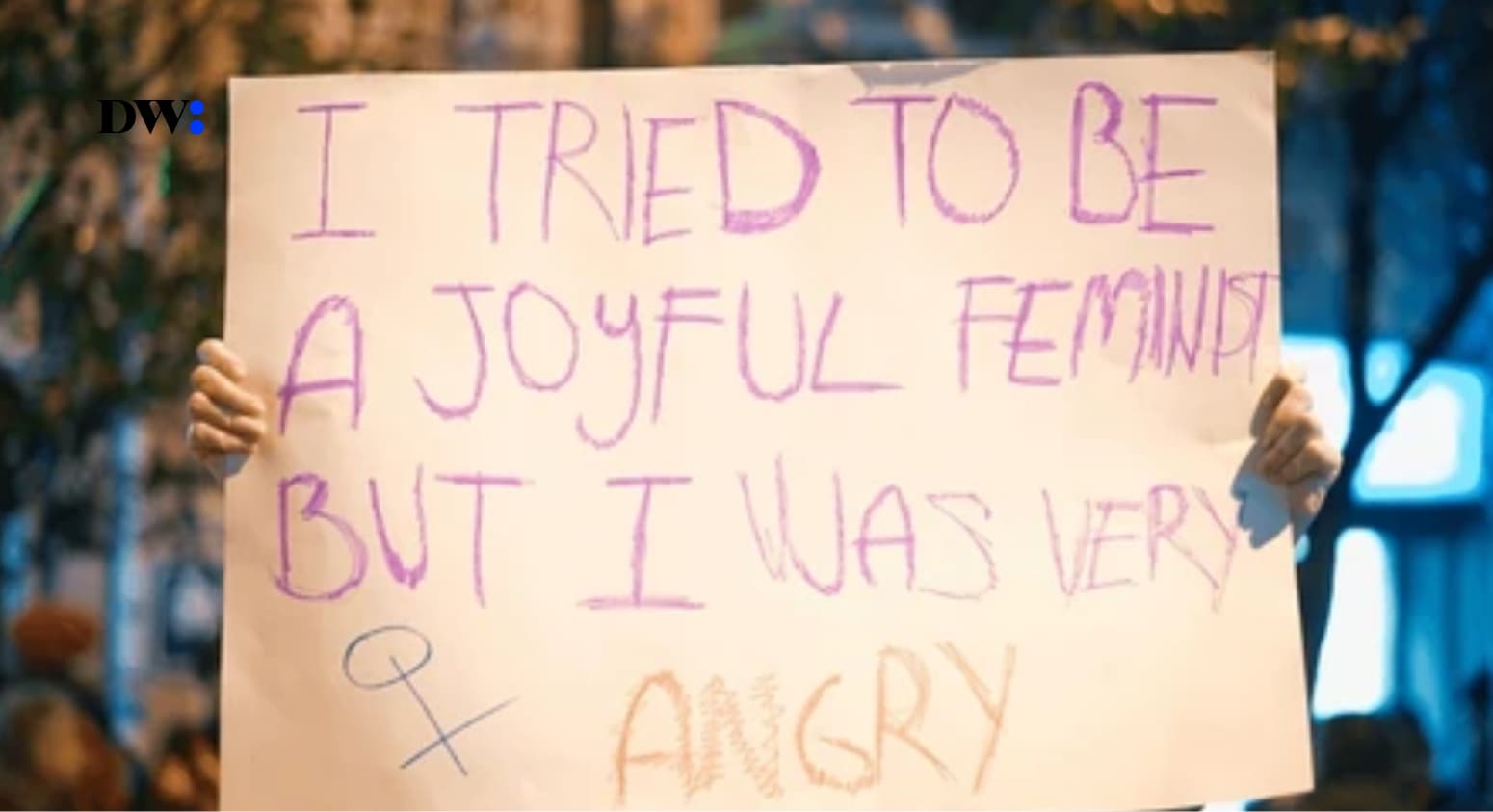

For Nigeria, the disappearing of memory most reminds me of the constantly denied deaths of #EndSARS, October 2020- You wonder why the inhabitants of the island did not fight back. Why did they not rebuild the disappeared boats or rebel against the Memory Police and the evil they perpetrated? It is here that I receive another lesson from the characters.

Before a revolution is a burning fire, it must first be a kindling. The kindness these characters showed to each other may be dismissed as daily life. But to continue to show little kindness here and there in the face of a bleak future with no assurance that there will be anything to remember is power- our protagonist clipping the overgrown nails of the fleeing professor’s son, the winter meals are shared by the trio of R, the old man and the novelist, The old man’s appreciation of R’s music box, even if he no longer remembered what value it held. Kindness keeps us going, and while “The Memory Police” speaks to so many things, the kindness it encourages will fuel the defiance needed to reshape empires.

“The new cavities in my heart search for things to burn. They drive me to burn things, and I can only stop when everything is in ashes”

This highly allegorical novel was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2020, and in exploring the relationship between love, memory, and identity, Yōko Ogawa tells a story that is undoubtedly a worthwhile read.