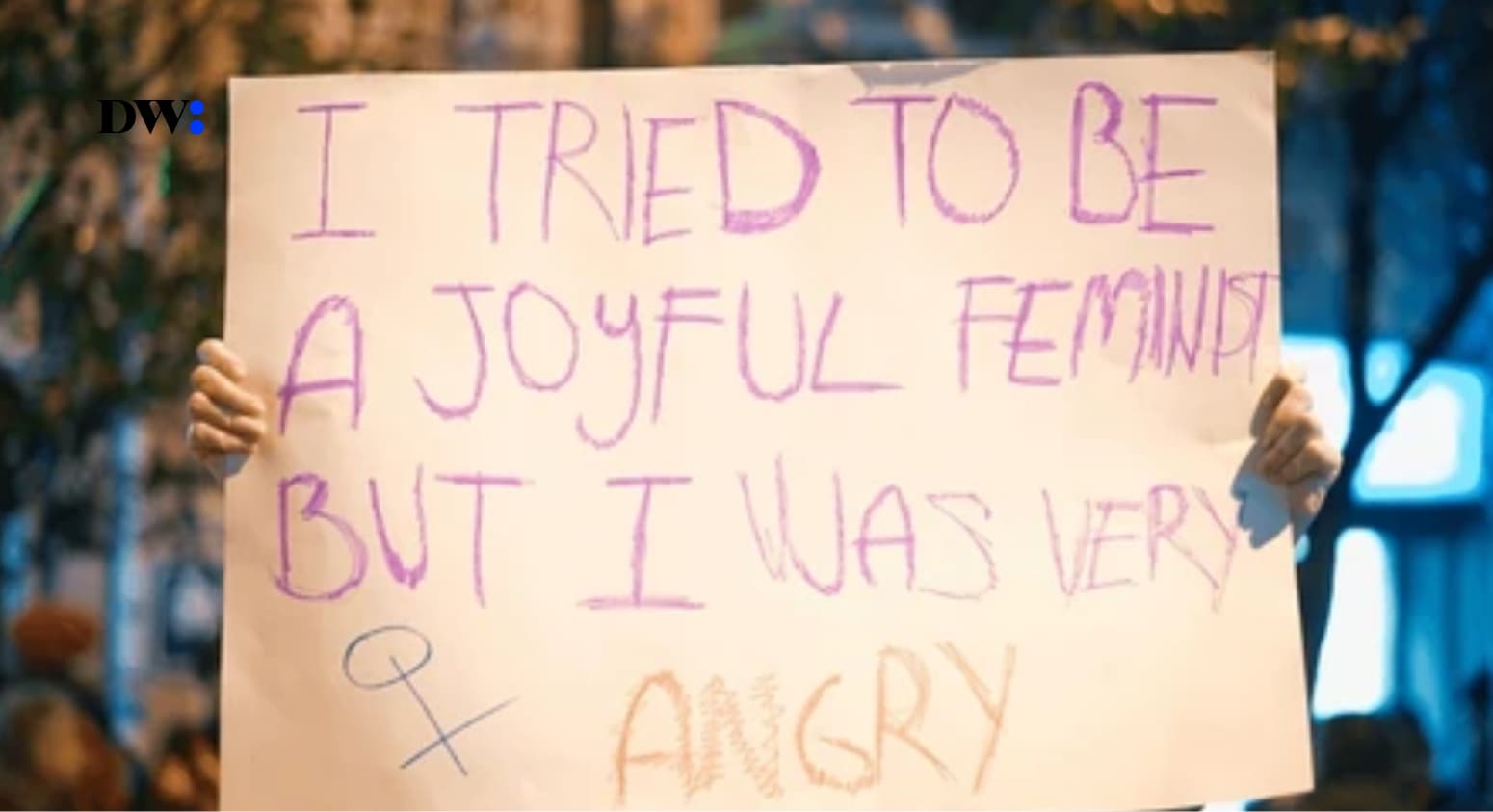

Medical gaslighting is surprisingly difficult to write about because even as the words form, I find myself wondering if I’m just being dramatic. If you are a woman, you might be familiar with that feeling; voicing your concern and being told that it is all in your head, sometimes you even start to doubt it yourself. Unfortunately, this experience of being manipulated out of your perceived truth, called gaslighting, is also present in healthcare, and women are often on the receiving end.

Medical gaslighting refers to when a health professional downplays a patient’s concerns. It could look like your doctor trivialising your symptoms, dismissing them completely, or attributing them to psychological factors without a comprehensive assessment. Regardless of how it looks, medical gaslighting often leads to medical neglect, which costs lives.

While gaslighting could be done consciously, oftentimes it is a manifestation of an unconscious bias. Research has shown that there is a gender disparity in the administration of healthcare, fueled by gender stereotypes.

Take pain for example. There is a gender disparity in the management of pain. A 2021 study revealed that a woman’s pain is perceived as less intense compared to a man and that perceivers were likely to prescribe psychotherapy for women and pain medication for men. Another study found that women who showed up in the emergency unit with stomach pain were less likely to be given analgesics than men who showed up with the same pain.

In May 2021, the news broke of the demise of Peju Ugboma, a Lagos-based chef. Peju had gone in for elective surgery, after which she suffered internal bleeding, which led to her death. Before she died, after her surgery, Peju complained of abdominal pain and discomfort, but because these are not uncommon symptoms following surgery, her complaints were not taken with urgency. Her blood pressure dropped drastically, the veins on her hand collapsed, and she had to be transfused. As her condition deteriorated, and she was moved to the intensive care unit (ICU), her husband sought a second opinion from a family friend, a UK-based consultant gynaecologist.

This consultant gynaecologist immediately requested to speak with the doctors in charge and told them that he strongly suspects Peju to be suffering from internal bleeding and that she required urgent surgery to arrest it. His opinion, like Peju’s complaints, was dismissed. Unfortunately, she passed on and her autopsy, according to her family, revealed 2 litres of blood in her abdominal and pelvic regions. It was apparent that Peju bled internally from after the surgery on Friday, until Sunday when she finally passed.

Peju is just one of many women who would still be alive if the doctors had paid their complaints a little more attention. Womanhood is a plethora of complex realities, and medical gaslighting is one of them. Our bodies are complicated yet misunderstood, and as a result, we lack accessible health information on our bodies. Women also experience socio-economic and political inequality, which makes it difficult for the average woman to access healthcare, and even when we do access healthcare, we are at a high risk of experiencing medical gaslighting and negligence.

We are disadvantaged and vulnerable, yet ignored. How many more women, like Peju, need to die before we start listening to them?