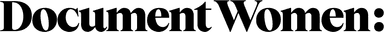

Mariama Bâ’s only poem “Festac…Souvenirs De Lagos” (“Festac…Memories of Lagos”) has been discovered by French literary scholar Tobias Warner, 46 years after it was published in L’Ouest Africain, a newspaper publication owned by her husband, Obèye Diop.

The Senegalese feminist author is widely known for her critically acclaimed novels So Long A Letter and Scarlet Song published in 1979 and 1981 respectively, and is greatly revered till this day as one of the foundational voices in African literature.

Her most notable work So Long A Letter, initially published in French Une si Longue Lettre is said to be one of the most translated pieces of African Literature of the 20th century, and played a pivotal role in the portrayal of African women in African Literature.

However, before Bâ would go on to write her most famous work, a trip to Nigeria representing L’Ouest Africain in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) birthed the poem that has gone undiscovered all these years. Warner discovered the poem after he came across a reference to the trip in an understudied biogriaphy Mariama Bâ; ou, Les allées d’un Destin (Mariama Ba; or, The Alleys of Destiny) written by Ba’s daughter, Mame Coumbs Ndiaye. He thereafter made a request to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for publications from 1977 written on FESTAC, with specifics on Mariama Bâ, in his article, he explained that the liberians had not found an article written by Mariama Ba but had found one written by a Mariama Diop.

Warner received the publication to the shocking realisation that Bâ had written the poem under her marital name, a possible reason why the poem may have gone unlooked all these years. Warner also found that Bâ had written several other contributing pieces to various publications, some of which included excerpts that later became part of her first novel, in his words it was evident that Bâ did not just “burst into print all of a sudden in 1979”

“Festac…Memories of Lagos” chronicles Bâ’s experience of the FESTAC festivities, detailing her impressions of everything, from the impressive colloquim discussions to the various inter-cultural displays of art, dance, drama, music. The underlying tones of excitement suggest nothing short of the spectacle FESTAC’77 must have been and can be seen in all the differeent ways it has been documented over the years. The poem also speaks of Lagos with hope of “rediscovered Negritude” and the remaking of a decolonised Africa, she proclaims Lagos to be a seed of pan-African rebirth.

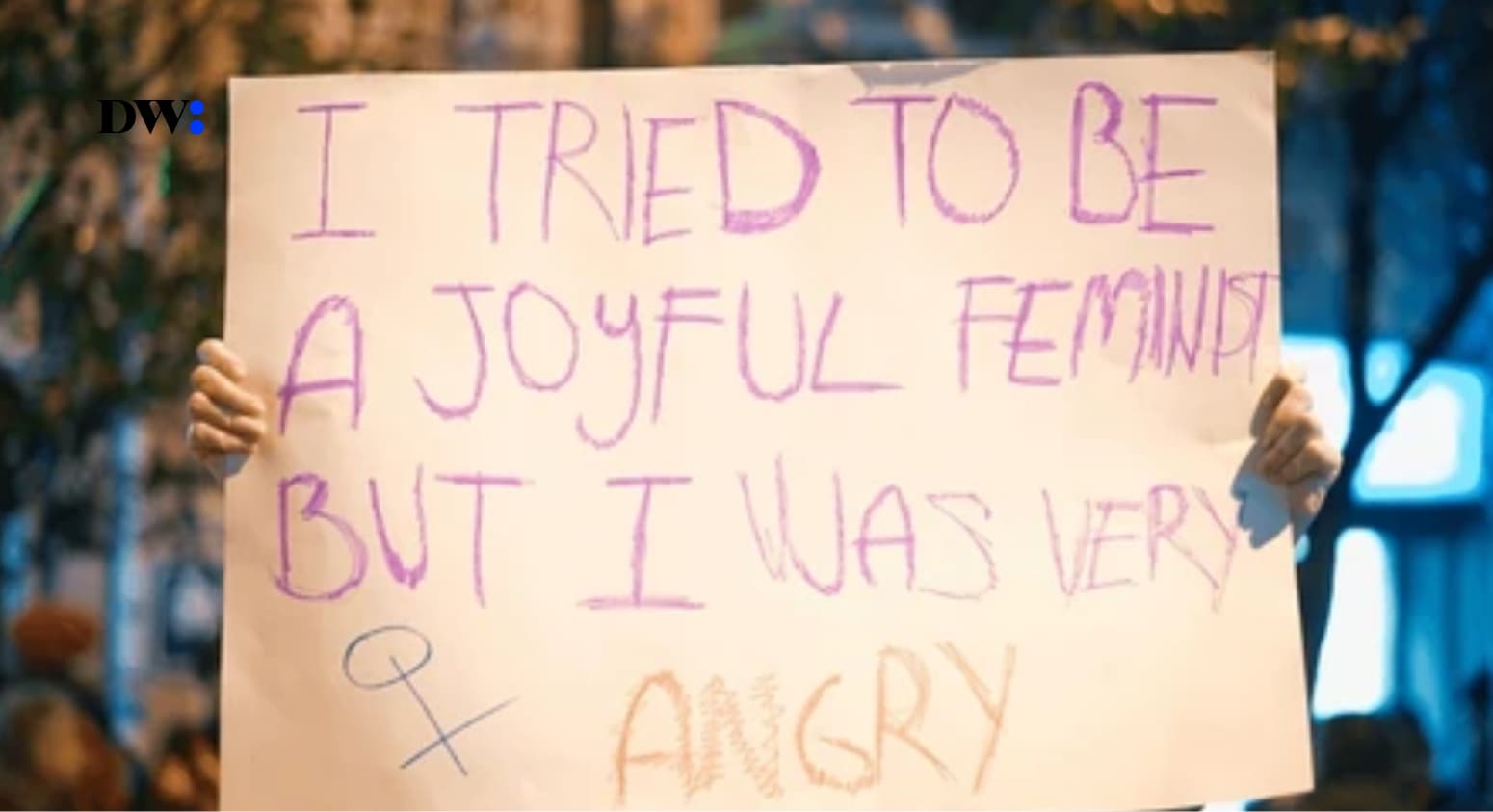

This entire spectacle has been a great addition to Mariama Bâ’s contribution to African literature and the depths to which her Oeuvre holds despite being cut short by her demise just before the success of her first novel and release of her second, yet it is a deeper call for a reflection on the ways women’s voices and identities get overlooked or drowned by the shapeshifitng nature of our nomenclature throughout our lives especially (but not limited to) by virtue of marriage.

It is also a wake up call to the unbalanced nature of technology and digitalization in our world today and how the arts and humanities are largely left out in these advancements. Just a few months ago there was a call for contributions to the digitalisation of Bessie heads literary archives, whereas there are tons of investments pumped into various technological advancements that are more profit-driven than impact-led, and if these problems are still peculiar to these developed countries, one can only imagine the number of publications in less developed climes that have been left unfound and gathering dust, documentations that may hold important aspects of our cultures and works of life that may never be discovered.