In February 2017, Samina Ali, an American author and activist, was invited to speak at the University of Nevada’s TEDx event. In her speech, she answered the question people have been asking for centuries: “What does the Qur’an say about a Muslim woman’s Hijab?”

She explained that during the time of Prophet Muhammad’s (S.A.W), women dressed differently according to their socio-economic status; the noblewomen wore jilbabs (coats) and the less fortunate wore fewer garments (because they could not afford jilbabs). The socio-economic class of a woman could be known by merely looking at her. Because of this, men knew not to approach women of certain backgrounds, so their prime targets (for sexual harassment) were automatically women from less fortunate backgrounds: the so-called “uncovered women.” This was the norm.

The issue was taken to the Prophet (S.A.W) who took it to God “and a verse was revealed for the Qur’an, the Muslim Holy Book,” Ali said. “‘Oh Prophet,’ it reads, ‘’tell your wives, your daughters and the women of the believers to draw upon themselves their garments. This is better so that they not be known and molested.’” The garment, which is now known as a Hijab, was a solution to the problem of discriminatory sexual harassment – so that the perpetrators (the men) would not be able to differentiate women based on their socio-economic status and use it as a basis for assault. In the other half of the verse, the Prophet (S.A.W) was instructed to: “Tell the believing men to lower their gaze and protect their private parts” (Qur’an 22:78).

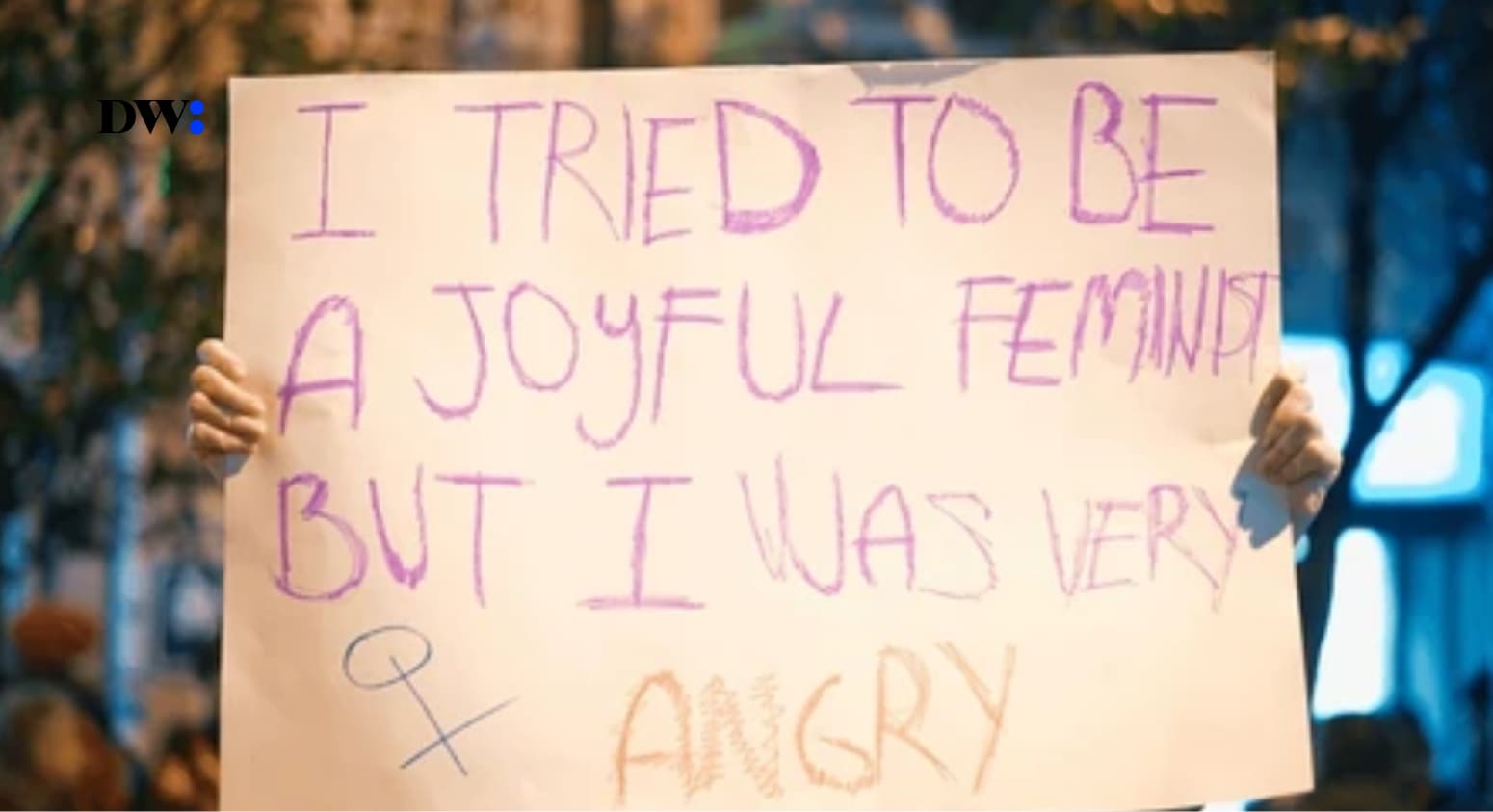

Universally, it is believed that a woman must dress “decently” to avoid being sexually abused and harassed. And “boys will always be boys” so if a girl is dressed immodestly, then she must be asking to be raped. But women still get harassed, even when dressed modestly. Just ask Sufiya Ahmed, who debunked this unfounded myth in her groundbreaking article: “Mayim Bialik, if you think modest clothing protects you from sexual harassment, you need to listen to these Muslim women”. In a conversation with the journalist, the chairperson of the UK’s Muslim Women’s Network told her:

“We receive calls on the helpline from Muslim women who disclose sexual assault and rape. They have been fully dressed. Some have been wearing a headscarf, jilbab (full robe) and even a face veil. The offenders have included family friends, family members, and also respected religious leaders in the community. Women’s dress is an excuse popularized by men to justify their behaviour so they don’t have to take responsibility. It makes me angry when some women join in and peddle the same narrative instead of challenging it.”

This is true for many Muslim women. In an interview with The World’s Marco Werman, Egyptian journalist and author Mona Eltahawy recounts being sexually assaulted while performing Hajj (Muslim pilgrimage) as a fifteen-year-old – something she speaks about extensively in her book, Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution. Following the #MeToo Twitter movement, she started a #MosqueMeToo movement to give Muslim women a platform to share experiences of being sexually abused or harassed in sacred places. While it was disheartening to see that this resonates with Muslim women worldwide, Eltahawy says that “it was really encouraging because Muslim women have a voice. And if we don’t hear that voice, we have to ask why? It’s not because they’re voiceless… it’s because they’re not often given a platform or usually, the men of the community pretend to speak for all of us.”

The conversation around the Hijab and the male gaze usually revolves around a woman’s refusal to wear one, while enticing a man in the process. People are always keen to chant the “boys will be boys” mantra, while expecting young girls to grow into women. By doing this, we are doing Muslim women a great disservice; we are telling them they asked for it, and that they deserved to be harassed depending on what they choose to wear. By doing this, we are destroying our girls and backing the men who are harassing them. The only question left to ask is: “How many victims must fall prey before we admit this to ourselves?”