There is no doubt that in recent years, Nigerian women have made significant strides in various sectors, particularly in regard to economic participation. The world has seen this in the rising number of successful female entrepreneurs, professionals, and leaders in their respective fields. Yet, in spite of their buoyancy in the workforce and the undeniable ability to generate income, true economic power in the hands of these women remains to be seen.

While the distinction between economic power—the ability to earn and manage money—and empowerment—the freedom to fully exercise one’s rights, make decisions, and thrive in society—may be perceived as seemingly thin, it remains crucial in understanding the broader challenges faced by Nigerian women and the rights that remain elusive to them.

Economic power necessitates a setting where women may completely exercise autonomy in all aspects of their lives. Contrary to popular opinion, empowerment alone does not always equate to economic power. Economic power affords access to opportunities, independence from societal constraints, and a voice in decisions that affect individual, collective, and professional futures. Empowerment, on the other hand, although often perceived as a symbol of independence, is far-fetched without economic power, as this would mean an absence of the agency needed to make a difference or influence others.

This is evident when women encounter cultural, legal, and systemic obstacles that restrict their access to resources and decision-making power, thus making it much more difficult for them to use their income for personal growth or to impact their communities effectively. One such cultural case occurs in the absence of a support system for balanced personal and professional pursuits. Without such an economic support system that recognises, acknowledges, and factors in women’s peculiarities and the broader need for success on both domestic and professional fronts, they are oftentimes forced to choose between their traditional roles as caregivers and career growth or entrepreneurial aspirations, thus limiting the full utilisation of their economic power in creating lasting societal change or achieving personal fulfilment outside the domestic sphere.

Additionally, on the legal front, although Nigerian laws are clear on women’s rights in regard to rights to properties, in many cases, women are excluded from land ownership or inheritance, particularly in rural communities where traditional practices override legal entitlements.

Studies have shown that over 80% of Nigerian women have faced a persistent challenge in securing rental properties as single adults. Several Nigerian landlords have been criticised for enforcing the “I don’t allow unmarried women to rent my house” slogan. Despite this, there has been a conspicuous lack of effective measures from the authorities to address and eradicate such discriminatory practices. This persistent exemption from property rights constrains women’s capacity to amass wealth or ensure enduring financial stability. Even women who generate their own income may encounter obstacles in investing in land or property, which are essential milestones in attaining genuine economic power.

Furthermore, the wage gap between men and women persists, with women earning 45% less than men in similar roles, despite having comparable qualifications and experience. Job discrimination, particularly in industries dominated by men or where women’s roles are undervalued, further limits women’s economic mobility. Another critical and long-relegated issue is safety and security concerns, particularly in urban centres and conflict-prone regions.

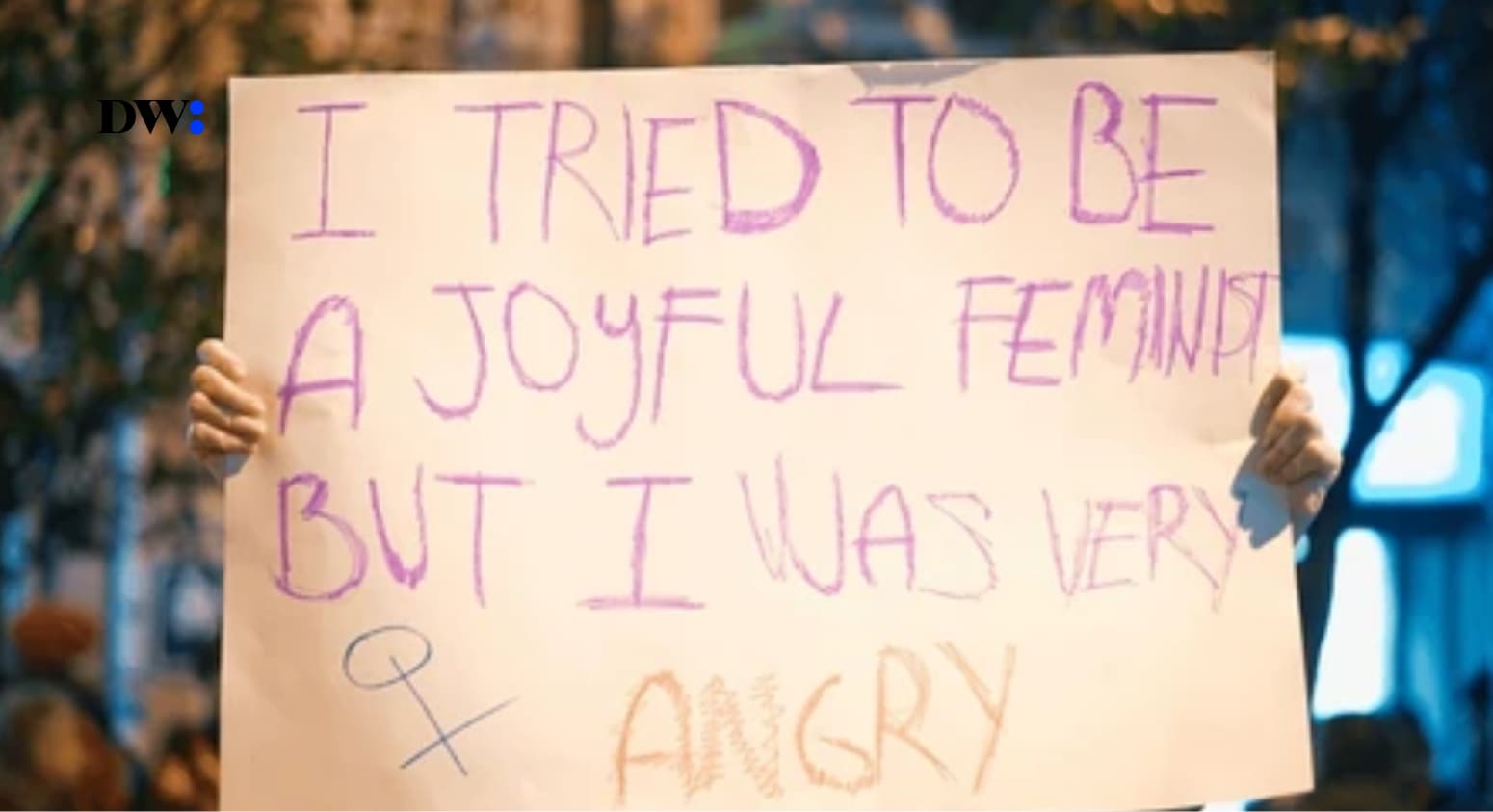

Despite economic success, the threat of violence—whether domestic, sexual, or political—often undermines women’s sense of agency and limits their ability to thrive. Women who experience violence or feel unsafe in their communities are less likely to pursue opportunities for growth and personal development, even if they hold economic power.

This concern for safety also significantly affects women’s participation in political processes, particularly elections. The fear of violence—whether from political groups, family members, or in the form of harassment during campaigns or voting—often prevents women from fully engaging in the political sphere. Women who are active in political campaigns or who wish to vote may face intimidation, physical abuse, or threats to their safety, particularly in areas prone to violence or political unrest.

This fear of violence limits their ability to contribute to electoral processes, as they are more likely to withdraw or stay silent to protect themselves and their families. Moreover, the absence of women from political participation, whether as voters or candidates, perpetuates the cycle of exclusion from decision-making tables, leaving policies and electoral systems that do not account for women’s specific needs and experiences.

There is also the issue of poor accessibility to financial resources, especially for women in rural or marginalized areas. Many financial institutions in Nigeria require loan collateral which women, particularly those without property or land rights, may not have. In addition, women are often less likely to receive financial literacy training, further complicating their ability to manage or invest their earnings effectively. The EFInA A2F 2023 survey showed that 30% of adult women were excluded from formal and informal financial services compared to 21% of men. This means that out of the 57 million adult women in Nigeria, approximately 17 million are financially excluded. This lack of access to financial resources stifles entrepreneurial growth and the ability to scale businesses, limiting their potential to secure long-term economic stability.

As previously inferred, these issues are often compounded by women’s exclusion from key decision-making tables in both policy formulation and economic planning which result in the establishment of policies that do not fully address their needs or challenge gender disparities. As we have seen, without representation in policymaking, women’s economic power is frequently undermined by the very systems that should be supporting their advancement, leaving them vulnerable to exclusionary practices and inequitable labour market conditions. Consequently, there is an urgent need to tackle this complex issue of economic power, which encompasses more than just financial independence.

In contemplating the path ahead, it has been repeatedly suggested that gender quotas for political representation be instituted, incorporating reserved seats for women within legislative bodies and party-level quotas to promote the candidature of women. Furthermore, it is essential that the electoral landscape be rendered more secure for women through enhanced security measures and the establishment of legal frameworks aimed at safeguarding women from violence and harassment in the context of elections.

It has also become imperative that legal reforms be prioritized to guarantee equitable access to political offices and to uphold anti-discrimination laws. To encourage women’s political engagement, public awareness campaigns and educational programs should be implemented. Additionally, supportive electoral infrastructure, such as childcare services, can be implemented to ease domestic responsibilities that may restrict women’s participation.

Ultimately, the involvement of male allies in championing women’s leadership can contribute to transforming societal perspectives and cultivating a more inclusive political landscape. These measures will collaboratively define a structure that enables women to maximize their economic power and engage more profoundly in the formation of Nigeria as a thriving nation.