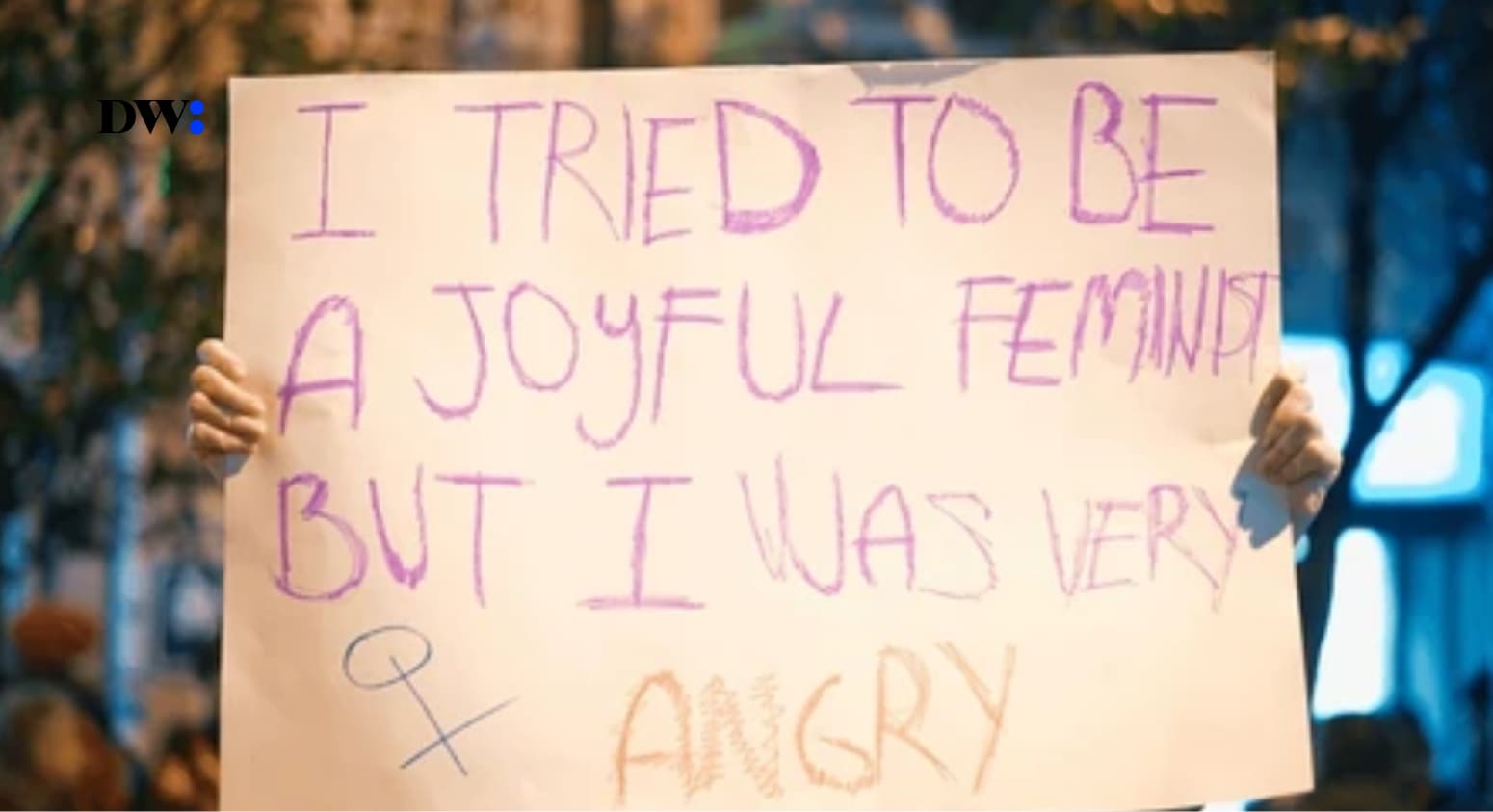

In Nigeria, women’s health issues often come with a heavy burden of stigma and silence. From the awkward glances at the mention of menstrual pain to the dismissive attitudes toward real medical concerns, there’s a deep-seated expectation for women to endure without complaint.

Drawing from my personal experiences, alongside interviews with other women, this essay delves into the troubling intersection of healthcare and misogyny in Nigeria.

1.

It’s 2012 or so. I’m back from school and I meet a bunch of our church members at my house; their bikes and cars parked in front of the compound, their shoes scattered by the entrance. I avoid stepping on them by walking on my tiptoes to enter the living room. I greet everyone and they chorus back responses. My mum is sitting on the central settee, looking tired but my siblings and I knew she had been “sick” for a while. I go into the children’s room and ask my brothers what is going on. They don’t know—the visitors just came one by one to greet mummy. I change into house clothes and go outside to play. After some minutes, our visitors troop out and some of the women come to give me advice. “Take care of your mother,” they said. “Don’t play with these children; go inside and look after your mum.” I would find out years later that my mum had had a bad miscarriage. None of us, her children, knew.

My mum is approaching menopause and is experiencing significant disruptions in her health. She has woken up bleeding on several occasions, has an irregular cycle, and her periods come unpredictably. Initially she started taking numerous pills and struggled to keep food down, which caused her to miss work for a week. When a friend visited and asked what was wrong, my mum simply said it was “just a bit of typhoid and malaria.” I observed them attributing her menopausal symptoms to mosquitoes, overlooking the real cause of her discomfort.

2.

In February 2024, I went to the hospital, scared of what I would find out was wrong with me. After an unusually long week of menstruating in December, I did not see my period for seven weeks. While I was waiting, I visited the hospital. I met a young doctor who looked at my file and asked, “Which school do you attend?” I told him I was done with uni. “That’s young,” he said. “So what did you say was wrong with you?” That rang a bell in my head. “It’s in my file,” I said.

“I’ve not seen my period this year and it’s never happened. I want to know what the problem is because everything on Google points to death—literally.” I told him I was scared I had PCOS because most of the symptoms I had matched, and I had been experiencing pain in the left side of my abdomen for a year. The doctor laughed and said I should get back to him at the end of the month before we conclude. No tests. Nothing. Was I sure I had not had sex? I said “Nope. No sex.” He said “Hmm, okay oh. If you say so.” I started to pack my things. “Come back later if it doesn’t show,” he said on my way out, “or you can come and be visiting me.” A doctor said that to me.

On a Saturday, after my experience at the hospital, my mum took me to see another “doctor” during his so-called “after-work hours.” This so-called medical professional used an iron instrument and a bunch of files, had me hold the instrument for three minutes, and then declared that I was syphilis-positive and had a “toilet infection,” fever, and “small typhoid.” I was stunned as he listed these diagnoses. He claimed I wouldn’t see my period again unless I “treated” myself. This man had been prescribing various drugs to my mum for months, treating her for multiple ailments. When we got home, I had a meltdown, and my mum stopped seeing him. I couldn’t stop overthinking my condition, but my period arrived two days later.

During the lockdown, in the dead of night, I experienced something I had never felt before. I had always been one of those women who only had periods lasting a maximum of three days. ‘God’s Favourites’. But that night, I woke up retching violently, as if I had something inside me trying to escape, throwing up nothing but air and the sickening stench of rotten eggs. My stomach felt painfully empty, and I crawled on the floor, writhing in agony. Words can’t fully capture the intensity of what I felt. My brother woke up to check on me, concerned for my well-being. By morning, my period arrived, gushing as if it were my last.

3.

Sonia* with a stellar health history, fell sick in April 2021. She went to her doctor who told her it was typhoid but she knew it had to be something else, and was referred to a lab technician on her insistence. After taking some tests, the lab technician asked when she was getting married. Sonia asked why. “I’m young, I’m 27. I’m not here for marriage, I’m here for a scan.” She just wanted to get better.

But the lab technician persisted. “Madam you need to get married,” he said. “Why?” Sonia asked. She was beginning to think marriage would make her healthy again. “Because of what we discovered,” said the lab technician, “because of kids.”

She took the result to her doctor and was asked the same thing: Madam, when are you getting married? One would think it was a part of their procedures in practice—to focus on unborn and imaginary kids more than their living patients.

“Is there no solution to this?” she asked.

“Well, you need to undergo a myomectomy procedure,” the doctor stated. “Now you’re talking,” she replied. Why were they talking about babies and marriage and how did they know she wanted any of that?

Because of what the doctor said, her parents began to push for her to get married, saying she was too young for a surgery but somehow, old enough to get married.

Before her surgery, Sonia* extensively researched myomectomy procedures and the common complications women might face. She explicitly informed her doctor that she wanted clean stitches and the highest standard of care, aiming to look at her body afterward and still feel good about it. Despite her concerns about epidural anaesthesia, which she had read could be problematic, her doctor assured her it was painless and essential.

Unfortunately, the experience turned out to be extremely painful for her, and she felt her concerns were dismissed, given she had the option to choose. Sonia* managed all her medical decisions and signed the consent forms herself, which she believes made her experience significantly different from women who had less control over their situations.

Sonia* finally had her surgery in 2024, but despite having one good doctor among a team of ten, the experience was far from smooth. She arrived for her operation with her nails and lashes done, only to be told by the nurses that she couldn’t go through with the procedure with her nails in place. This information was not communicated to her before the surgery appointment. As she attempted to remove them, she accidentally pulled off a nail. When she consulted her doctor, he advised that she could simply trim them to a shorter length.

However, the nurses were still dissatisfied and began to criticize her for having worn nails to the surgery. They also made derogatory comments about her locs and body. Sonia* had hoped for at least some compassion, but instead, they seemed to judge her for not fitting their ideal image of a patient. To them, she didn’t appear pitiable enough to warrant any empathy.

During the post-surgery check-up, she told one of the doctors that she was feeling pain. The doctor was dismissive, but she stood her ground.

“I know period pain and surgery pain, but this is not it,” she maintained.

After undergoing surgery, Sonia* had a urinary test that revealed she had developed a Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) due to the catheter used during the procedure. She frequently reflects on how she had to be persistent and assertive, feeling dismissed because of her gender, with her pain often brushed off as “normal woman” discomfort. While her “good doctor” did adjust her medications after she reported side effects, she still faced challenges with some male doctors and female nurses.

Just a day after her surgery, Sonia* struggled to walk to the bathroom due to severe pain, waddling awkwardly. Female nurses reprimanded her to stand up straight and walk properly, seemingly oblivious to the fact that she had just undergone major surgery. As she returned from the bathroom, she overheard the nurses discussing a woman who had a C-section and then went home to prepare amala that evening—labelling her as a “very strong woman.”

Sonia’s Head Surgeon tagged her as a “very stubborn girl!” She doesn’t mind the label. She believes you have to be very persistent and embrace agbero mindset or they will walk all over you.

These stories highlight how societal pressures and medical misogyny shape the way women are treated in hospitals and clinics, exposing a need for more empathy, understanding, and real change.