Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, popularly referred to as the first Nigerian woman to drive a car, is one notable Nigerian female figure that I’ve always known about. However, in my quest for feminism I discovered years later that she was a suffragist and strong advocate for women’s rights in Nigeria in the 1940s.

This makes one wonder why a powerful force like her was merely reduced to the first woman to drive a car in Nigerian history. This is just one of the many instances in which the activism of women in this country is under-documented.

The history of activism done by Nigerian women go as far back as the precolonial era. Worthy of mention is Queen Amina of Zazzau who ruled Zaria in the 15th century and Ebele Ejeanu who founded the Igala Kingdom. In fact, the very year Nigeria was amalgamated, a group of women staged a protest called the “Ogidi Palaver” against indigenous and British men for sidelining them in decision making.

There was also the colonial era Aba Women Revolt (1929) where market women protested against the heavy taxation imposed on them. The pre-independence and post-independence era witnessed a rise in organized women’s movements. Among them was the Abeokuta Women’s Union, Nigerian Women’s Party, Federation of Ogoni Women Association and Women in Nigeria just to mention a few, all which aimed at the liberation and socio-economic improvement of the lives of women.

Till date, women are still actively fighting for their rights and making voices heard through various platforms like NGOs and social media. NGOs like Women Advocates Research and Documentation Centre (WARDC), Feminist Coalition , SirenCo , Girdle Advocacy Projects and some outspoken feminists online like Doreen Uloma Nwoke , Angel Nduka-Nwosu, Ozzy Etomi use their platforms to center women’s voices and issues. These movements that have spanned decades encompass women from various spheres of life irrespective of their backgrounds.

Tayo Agunbiade, a women historian and author, once said in an interview that “women stories are too often just mentioned in passing”. This is the case of the activism done by women in Nigeria. There is a gross under documentation of the efforts that women have made over the years in fighting for their rights. One prominent way is the complete reduction of great feats accomplished by various women activists to trivial achievements.

The Aba women revolt of 1929 for example, is usually downplayed to just a group of women protesting “naked” in modern narratives. The complete erasure of women’s activism in Nigeria’s history is another way these efforts go unnoticed as their names and achievements are not very present in Nigeria’s history books.

Talking to Doyin Alana, she says this said erasure started from the school curriculum. In her words “Women activists I got to know were outside the walls of school. I was only taught that Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was the first woman to drive a car and eventually died brutally”. The media also plays a role in diminishing the works of women’s right activism as they usually ignore and under-report women’s campaigns and protest especially when those activities are not centered on issues affecting men or the general populace.

On this, Angel Nduka-Nwosu, a writer and journalist, says that women centered protests don’t get as much coverage as other protests because the main victims are not men, she cites the EndSars protest as an example.

“I was one of the organizers for a series of protests on police brutality against women that had happened a year before EndSars. It was called #SayHerNameNigeria . The whole point of the protest was to address how the police had rounded and locked up about 100 women in Abuja,” She tells me. “The police had asked them to pay N5,000 or sleep with them (rape) for bail. It didn’t receive the level of amplification that EndSars had because the main were women unlike EndSars where the most visible victims were men”.

We cannot talk about any aspect of Nigerian women activism without talking about the women that walked so as other activists will fly. The unsung and forgotten heroes who sacrifices have been forgotten. We must remember Charlotte Obasa and Lady Oyinkan Abayomi who were champions of equal rights and education for women and girls in Nigeria in their respective lifetimes.

Chief Alimotu Pelewura had also led several protests with market women in Lagos concerning various injustices meted out on them. Women like Mrs. Amelia Osimosu and Mrs. Eniola Soyinka who alongside Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti led the members of the Abeokuta Women’s Union to stage a revolt in 1947 against the then Alake of Egbaland.

The fiery efforts of Margaret Ekpo is to be remembered as she had fought for and mobilized women in eastern Nigeria. There’s also Gambo Sawaba, pioneer women’s rights activist in the north who advocated for education, jobs, and voting rights for women. She also openly spoke against child marriage, forced labor and unfair taxes for northern women.

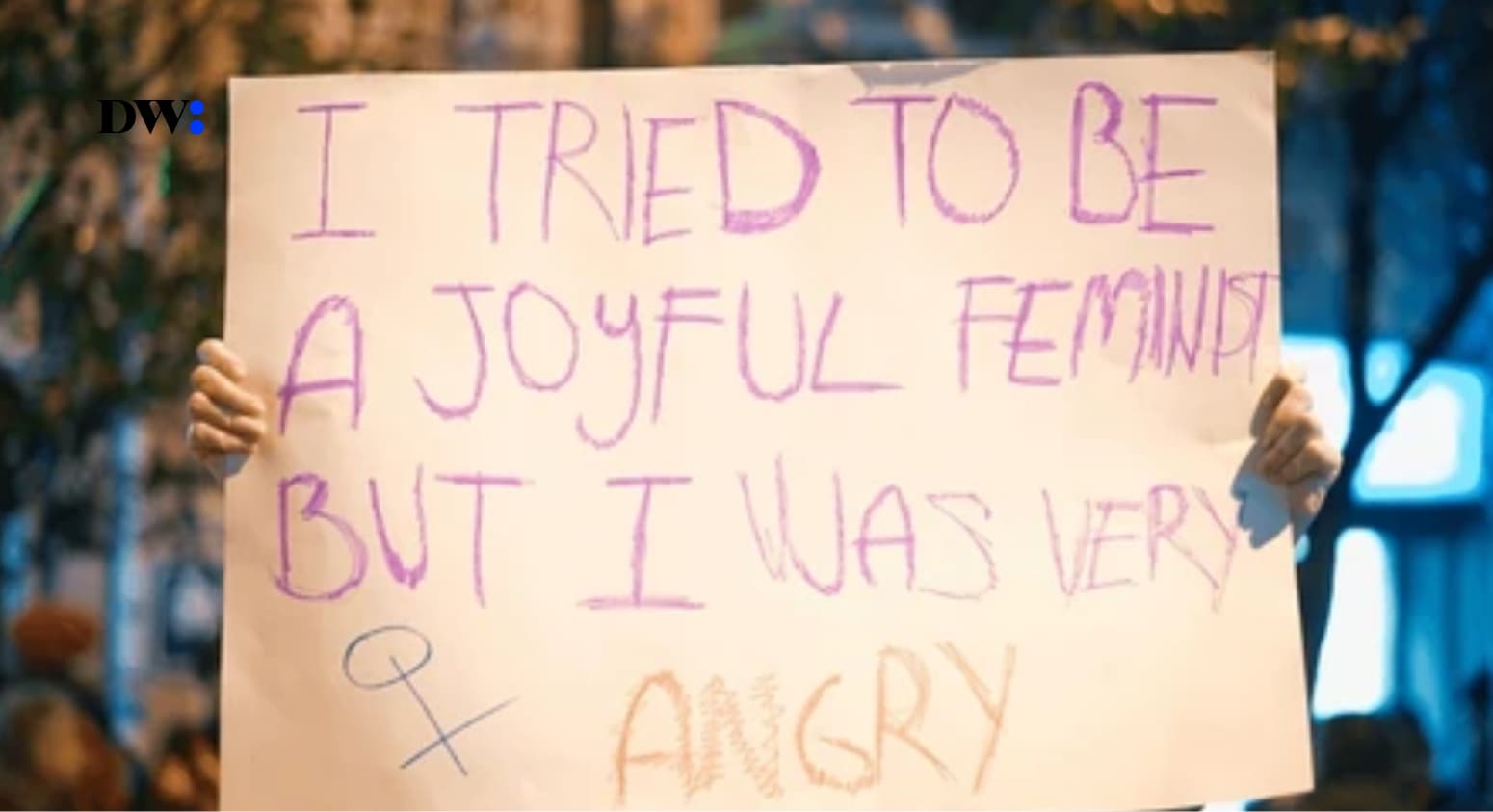

As progressive as we think this country might be today, the women’s rights activists and feminists of this era also face some challenges in their efforts being recognized. Women’s activism is sometimes met with mockery and levity. This is seen when certain “women’s issues” trend on social media and feminists weighing in on those issues earning the derogatory line of “what are the feminists doing about this?”

Speaking with Omolola Pedro , a SGBV activist, she says truly women’s activism is not properly recognized in Nigeria.

She tells me, “The Nigerian system undermines everything (about) women. Little or no recognition goes to their efforts, because why is Aba Women’s Revolt against high-handedness called a riot, when there are instances when men didn’t do as much and they gained relevance in our books of history and current affairs.”

The under documentation of women’s activism in Nigeria is just deeply rooted in patriarchy. Nigeria is a society that thrives strongly on patriarchal norms and standards. In a society that upholds harmful gender roles for women, when women fail to conform to these roles and fight for their rights, they are overlooked.

And even when they struggle to get what is deserving of them, these efforts are often overshadowed by traditional gender roles of being homemakers and supportive partners. Also, Nigerian history is male-dominated, those who write and preserve these stories are men, and they control the narrative.

Men’s achievements have always been prioritized, with women’s achievements left as an afterthought as it is usually dismissed and considered trivial. It is for reasons like these that women’s activism is not properly recorded in historical books and archives.

Furthermore, men taking credit for activism done by women drastically reduces the chances of women’s efforts to be properly documented. There have been instances where men come into activism spaces created by women to “support”. When they are allowed in, they always try to center themselves and spearhead the movements themselves. When these men are seen in these spaces, the narrative that they are in charge, that they are the backbone of such movements are easily pushed and sustained.

Speaking with Idayat Jinadu on this she says that “There are attempts to sabotage women’s efforts and it’s done by men who suddenly get the “idea” to do something that a woman has already done. E.g, the Opeyemi guy who wanted to do sex for grades documentary, that has been done by a woman in the past”.

When we fail to document the stories of women, their efforts and activism, we fail to create role models for the next generation of girls and women. The exclusion of women’s activism from historical records further supports the notion that women are not capable of doing anything for themselves without the influence of men.

Documenting women’s activism is crucial for women and the society. By doing so, their sacrifices are properly recognized and acknowledged. The wide gap in the male-dominated historical narratives is also bridged, as there won’t be speculations as to who did this and who didn’t. The significant impact of properly recording and documenting women’s activism also plays a key role in inspiring young women and girls to make their own voices heard in the activism space. Young women are more likely to participate in activities that will bring changes to their lives if they learn about other women that have done so in the past. Documenting women accurately also helps provide data and statistics that can influence policies and laws that improve the rights of women.

The stories of activism done by women must be properly told and written. Women’s voices need to be amplified on all levels, not as extensions to men’s achievements but solely as their own fights and efforts. For every initiative or idea founded by women, men should not and never take credit for it. History should not be written in a way that completely erases women’s efforts. On this, Doyin posits that women heroes should be introduced into educational systems.

We need to start writing women’s activism stories by ourselves, to change the narrative of a male-dominated history. Women’s activism needs to be preserved better in historical records and archives. For Idayat, she says “what can be done better to document women’s voices and activism is by writing it, putting it online and making it public”.

Women’s activism should be properly portrayed in literature and media. Recently a biopic of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was released. More films like that should be produced to showcase the struggles and efforts of women’s rights activists. June 12 is a day that commemorates the death of Chief M.K.O Abiola, why don’t we have days like that set aside to celebrate the struggles of women’s activism?

Women’s activism deserves to be seen, heard and documented properly as it should without undermining and erasure.