In this eye-opening episode, we sit down with Dr. Tim Nutbeam, a leading expert in Emergency Medicine, to explore his groundbreaking research. The findings expose a startling truth: women seeking emergency care are subjected to different treatment than men, with potentially life-threatening consequences.

Read and listen to the episode below:

Rihanot Ojo-Oba: Welcome back to The Counter Narrative, a platform where we delve into thought-provoking discussions. I am Rihanot Ojo-Oba, and with me is the incredible, amazing, beautiful, and talented Tiara Oluwabukumi-Fadeyi.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Hi, Rihanot. Hello, listeners. Today, we’re thrilled to have with us Dr. Tim Nutbeam, an NHS emergency medicine consultant, the medical lead for Devon Air Ambulance, and a clinical academic in emergency medicine.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

Dr. Nutbeam’s extensive experience in emergency medicine and critical care, coupled with his academic work, makes him a highly respected figure in his field. Let’s dive into our conversation with Dr. Nutbeam.

Dr. Nutbeam. Hello.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Hi, Dr. Nutbeam. It’s good to have you here today.

Dr Nutbeam: Hello. Good morning. Many thanks for having me on the podcast.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba: Good morning.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: Could you debunk two myths about women’s health care that is not backed by science?

Dr. Tim Nutbeam:

So, I think the two myths which are worth talking about today are, one, are women the weaker sex, and two, that health care is equitably distributed. So, science shows us that women are the weaker sex.

They do much better from birth up until old age, whether it be response to disease or infection, whether it be traumatic instances, whether it be preterm babies. Women seem to do better, and they seem better genetically prepared to deal with what life throws at us. The second point was around equitable health care.

So, I think we imagine that health care is distributed equitably between males and females. And that the health care system is tuned to both males and females and whenever we study this, whenever we look at it, we realize that this isn’t the case. And whether it be due to biological factors or gender-related factors, or often the health care system’s response to such factors, women tend to have not equitable access to health care.

For example, pain medications, chest compressions and CPR, or access to medicines such as tranexamic acid when they’re bleeding.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Thank you for your answer.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

I think calling the women the weaker sex, women bring life into this world. So, imagine calling a woman who goes through pregnancy, labor, delivery, postpartum, the weaker sex.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Even menstruation.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

Exactly. Imagine calling someone like that, that goes through all of that, the weaker sex. I don’t think that word should exist anywhere in the world. That’s ridiculous, you know.

In your clinical investigation about tranexamic acid and major trauma, it was found that women are less likely to receive TXA than men. What, in your opinion, causes this disparity?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

In this study, we looked at major trauma patients in the United Kingdom. So, people who had major injuries and one of the things that we like to do if someone’s got a major injury is give them this medicine, tranexamic acid. And it helps stop bleeding. And we know from big studies that we’ve carried out throughout the world, that it helps reduce the chances of you dying if you’ve had an injury.

We looked at the Trauma Audit Research Network, which is a big database in the UK, which captures outcomes from all trauma patients and we looked at the difference between men and women. And we were shocked by what we found. So, we found that women were half as likely than men to receive this life-saving treatment.

What does this study show? It’s important. The study just kind of shows this. This relationship. And it breaks it down. And we can see the relationship, whether it be a car accident, or whether it be a high-level fall, or whether it be a stabbing incident. What the difference is between men and women and women are always coming off worse in terms of access to this medicine.

I think some of it is due to how we’re taught in medical school, and the stereotypes of what normal trauma is. So, many of the ways that we’re taught, and many of the manuals that we have access to, use males as an example. So, if you attend a trauma course, or if you have a look in your manual, it’s often a young man that’s been injured. And as such, I think our healthcare systems and how we are, kind of our approach, is tuned towards looking for trauma in that age group.

Many of the studies that have been conducted have disproportionate males in them. So, particularly pre-1980s, pre-1990s, most studies were conducted on white people, and most studies were conducted on white males, particularly. So, a lot of our learning from healthcare is tuned towards males, and towards the white male group, particularly.

Obviously, there’s been lots of work by groups like Gendro to help surface this, and also address this moving forward. And things are, they’re not perfect, but they are much better now than they used to be.

So, I think there’s lots and lots of factors. So, there is what is considered normal trauma, how we train and educate our trauma professionals, the mechanism of injuries that women suffer are slightly different from the mechanisms injuries of men, and yeah, that creates these biases.

I think it’s also important, there’s a lot of unknowns out there, so we do need to investigate it further, and see perhaps is there an issue with the gender of the caregiver, compared to the gender of the care receiver. So, much more work needs to be done, but it’s a complex area that our finding is shocking and worthy of further investigation.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Okay, thank you Dr. Nutbeam. So, recently I read a tweet where the person went to remove a problematic tooth, and her husband did the same thing in the same hospital, but then she was given a lighter painkiller than her husband was.

They gave him a stronger dose, and they gave her something light just for the pain. So, there’s this perception that women exaggerate pain, like they are hysterical,

and that they handle pain better, which I think is responsible for the lower level of painkillers they give women and men in the same situation.

Is there science to back up this perception?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Uh, so we know that women are less likely to receive adequate pain relief than men. My expertise lies in the emergency scenarios, and we know that women attending the emergency department are less likely to receive the same painkiller milligrams per kilogram compared to men.

We know that these painkillers are as effective for males and females, and yeah, it’s difficult to investigate people’s individual pain experience. But when we do have a look at people’s individual pain experience, whether you use a pain score or whether you use another marker, we are less good at treating pain in women.

So, I think we need to separate out people’s pain experience and their individual toughness to pain, or how resilient they might be to pain, and the healthcare system’s response to it. Uh, and painkillers should be titrated and offered equitably, regardless of your sex or your gender, uh, based on your pain needs rather than any of those other factors.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Okay, so if I understand you correctly, you’re saying that there’s basically, there’s no scientific backing for saying women handle pain better, women are exaggerating, and men are less likely to take pain, or to undo pain better.

It just depends on the individual involved in that situation, right?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Uh, yes, that’s my interpretation of the science available in this area. People’s pain’s response are different, uh, and the effect of gender and sex, uh, isn’t an issue. We should be tailoring care to the patient in front of us, and their individual pain experience.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Okay, thank you for the answer.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

I think it’s ridiculous to say that women are the weaker sex, and then in the same line, you say they handle pain better.

How, it’s, it doesn’t make sense.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

The patriarchy is very ironical and funny. It’s deeply rooted, honestly.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

And you know, it’s like the conversation we have about, oh, head of house. As the head of house, you should be in charge of the house. Why is this the same weaker sex that has to do childcare, domestic labor, nine to five, and everything? It’s, you know, the patriarchy, the patriarchy is, is very funny.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

It is deeply rooted, and you know, people do not see this, like, it’s like they utter it before they realize, oh my God, that didn’t make sense.

How are you saying somebody is weak, but they should be the one to carry more burden in a household?

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

It’s ridiculous to be honest. It is.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

Away from that, female healthcare professionals often face gender bias, gender bias and harassment. As a feminist ally, how do you address these issues, particularly with male colleagues who may not be as aware?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Uh, so, we all know that gender-based is not, uh, gender-based issues and misogyny, uh, exist in every workplace to, to a various extent. Uh and we all have a role in trying to challenge these behaviors and try to, to move things forwards. Um, healthcare, uh, despite being an environment where a majority of the employees are women or females, um, is certainly, uh, not exempt from this. And we have our own issues, uh, in the NHS.

I think there’s lots that we can do. So, uh, education is really important and raising awareness of these issues, making sure that people are aware of the importance of, uh, you know, training in diversity and inclusion, make sure people really understand what unconscious bias is and what misogyny is and when kind of microaggressions do occur or inappropriate behavior does occur, kind of, we need to tackle that and make sure that we tackle that effectively.

I think leadership is really, really important and have, kind of, women modeling what good leadership is, uh, and, um, setting a positive tone in the workplace is a really important bit of how we raise these issues and how we promote these issues and and make our workplaces move forward in this area.

Um, and obviously as part of that, we need to ensure that we’ve got diversity in those leadership roles, whether that be diversity by gender or sex, or, racial background and all the other things which we know that, uh, power is, is related to.

Um, of course we need some degree of enforcement and that needs good policy, good HR policy, um, and, and that needs to be clearly communicated. So people, people know, uh, what’s acceptable and more importantly, what’s unacceptable. And we need lots of ways of reporting when these behaviors occur, whether that be to a friend, to a buddy, whether that be through a formal HR program, whether that be through our line manager, um, there’s lots of stuff as well around how we organize our workplaces to make them, have equal opportunities for men and female, uh, for males and females. So, uh, one of the issues that we have in medicine is that it’s a very full time or more than full time culture.

A lot of the training opportunities, um, occur in people’s life cycle when they’re just thinking about starting a family and having children and many of our workplaces and training schemes involve moving around the country or moving around the world or extended periods of travel, which just don’t fit with, uh, you know, uh, having a baby, and actually how we kind of promote work-life balance, how we create equal opportunities and how we kind of build these into how we advertise our jobs, how the jobs are related in terms of travel, time and, and all those other things, which actually make them genuinely equal opportunities to males and females.

I think it’s important that we keep an eye on these things and we understand when these incidents occurring, we hold perpetrators accountable. We report these incidents. So it becomes part of a culture of learning. Um and then I think the thing that we often forget is that we forget to seek feedback from our employees. We don’t ask them, how can we do better? Um, how can we do better in addressing these incidents? How can we do better in building a safe and inclusive culture?

So there’s lots, I guess in summary, there’s lots and lots of stuff that we can do and I think we’ve made baby steps in the workplaces that I work in, but there’s always more work to do there.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Okay. Thank you for, for that robust answer because you touched on a lot of things, the policies, the, um, personal, the interpersonal part of it. I don’t know. So thank you very much for that.

So I’m going to take you back to one of the things you first said, when we got on this conversation, you mentioned that a lot of the research for a lot of medical research are tailored for men and mostly white men.

So it leads to people saying stuff like the woman’s body is a mystery, stuff like that. Like they say things like that. It was just recently I read a research article talking about how the pain from childbirth can be equated to a gunshot in the leg.

It was recent. It was a recent research and you know, it was funny to me because women complain about childbirth and how painful it is, but it took a team to just, it took a team to go and do the research recent, I think it was last year or this year that it just did the research.

So a lot of things about women are not understood because clinical research does not focus on that.

So how do you think we can bridge this gap where we have more knowledge on the workings of a woman’s body? How do you think we can bridge the gap? And do you think, do you see a future, like a near future where this is going to be possible?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Um, so there’s lots of aspects to that question. And many of the answers, I guess, are similar to, uh, the answers around how we tackle misogyny in the worst place, because this isn’t about workplace misogyny.

It’s about research misogyny and how we tackle that is probably in similar ways. And I’ve seen some excellent work done by groups like The Lancet and Gendro around tackling some of these issues.

So, um, we need to put women’s health on the agenda. We need to ensure that when we publish studies, that we publish the outcomes for men and we publish the outcomes for women. Funders of studies need to ensure that if it is, they know that there’s equitable funding for conditions, which affect men like prostate cancer and issues which affect women, whether it be childbirth experience or whether it be many of the other potential health issues.

Um, I do see real steps moving forwards. many of the major health journals now have a gender inclusive policy. They have policies around what work they publish.

They ensure that women’s health is equitably represented, and it’s the same for the funders and it’s the same for the universities.

So I do see some real positive steps, uh, moving, uh, moving forwards. And once again, uh, we need policies which support that. We need to analyze data. We need to look at what is published and if it is fair and equitable and call out when it’s not, and we need to seek feedback and say whatis missing from our understanding of, of women’s health. Uh, once again, uh, we’ve made some steps forward, but there’s much work to do.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

You know, speaking of women being overlooked, there was a time where it was not acceptable. It wasn’t okay for a woman to say that she wanted to, she wants to be a doctor. It was seen as a taboo because why do you want to be a doctor?

You can be so many things lesser than being a doctor. Besides, if you’re a doctor, who is going to take care of your children? Who is going to cook for your husband? We still have this conversation. You hear people in conversations? They’ll say that, “ you want to be a doctor, who is going to care for the home?” And it makes women not even want to practice medicine because we’re not seen as people that should achieve the status of caring for other people by being doctors because someone has to stay home to watch the children or something as simple as cooking.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

And it’s so funny because the woman is a caregiver in the house. Yes. And being a doctor is more about giving care. Yes. It makes no sense to say that women can’t be doctors, but they can give care in the house. So it’s like women can, it’s the same thing with cooking.

Women, we have more male chefs in the world. (Well paid). That we have women, but women are the ones supposed to be the ones doing the cooking. It’s just really, it’s ironical. (It is actually) Yes. It’s always, it’s always really ironical. Yeah.

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

And we are, we are seeing change in that. We are seeing change in that area. So, between 75 and 80% of medical students in the UK are women. So, you know, and we’ve still got many leadership roles in the NHS taken by men, particularly white men, but we are seeing that change. And we’ve seen really, really good work in terms of inclusive workplace policies, women in leadership roles, community engagement, like STEM education, many things, which are helping us to address this balance.

So I completely understand and have empathy for the challenge that you’ve described, but I think we are, we are moving forwards in, in that role. And particularly in the UK, I think it’s well accepted that, you know, women are excellent doctors and, and that gender disparity has all but disappeared.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

That was, that was very enlightening. You published a paper on gender differences, and motor vehicle collision outcomes. Can you share the motivation behind this research, your key findings, and your thoughts on why certain injuries are more common in women?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Okay. So I’ve got an interest in post-collision care. So everything which happens following a motor vehicle collision. So when you have a motor vehicle collision, you have a transfer of energy and sometimes that’s uptunded or made smaller by a seatbelt or an airbag or a crumple zone. And then you’ve got the individual who’s in the car as well, and now have their own propensity to get injured based on their, their sex, based on their age, based on their comorbidities, you know, and perhaps how frail or fragile their bones are.

And that’s my area of interest. And I was particularly interested. I’ve done a range of studies looking at different aspects of motor vehicle collisions. And I read a book, which I’d highly recommend called “Invisible Women” and it talked about many of the factors that we’ve talked about today, about the issues with people underreporting the difference between male and female outcomes.

And I had this big data set with 70,000 road traffic collisions in. And I thought, I’ll take a look and see if there is a difference. And there was and then we investigated that further using various statistical tools. So what did we find?

So women are more likely to have injuries of the pelvis and more likely to have injuries of the spine. And in many other ways, the outcomes are the same. However, one of the key findings was that women were much more likely to be trapped following a motor vehicle collision. So following a motor vehicle collision, you can imagine that sometimes the shape of the car changes around you and that leads to entrapment. So you’re more likely to be stuck in the car. And we know that those people have worse outcomes. They’re more likely to die.

So why, why might this be? Why do women get more injuries of the pelvis? Why do women get more injuries of the spine? And why are women more likely to be trapped? I think this is, there’s multiple factors here, some of which are biologically related and some of which are gender related.

So the biological factors are, is that a woman’s pelvis is different to a male pelvis. And a woman’s spine, particularly the ligamentous aspects of the spine, the ligaments, is different to a male spine. But the rest of it is probably gendered behaviours.

So women are more likely to have a side impact collision. So they’re more likely to be hit from the side. Whereas men are more likely to be hit from the front. And when you have a side impact collision,

you can imagine that that might crush your pelvis or squeeze your pelvis. And also, it’s more likely to involve the door. So you’re more likely to be trapped.

However, I don’t think that’s the main problem. I think the main problem is that cars have been designed around a male norm. So car testing, the safety testing for cars is based around a 70 kilogram male mannequin, not round a female anthropomorphic mannequin. And often when you test a vehicle from a safety perspective with a male mannequin, and then a female mannequin, their safety rating drops very, very significantly. And it’s only recently that female mannequins, so female crash test dummies, have been used to test cars.

So effectively, your car is set up to look after a man, and it’s not set up to look after a woman. And as a result, women are more likely to have significant injuries,

and women are more likely to die in the same motor vehicle collision. There’s a secondary thing as well, and it’s about how we kind of distribute safe vehicles in an inequitable way.

So if you get a traditional male-female partnership, the male is more likely to drive the modern car, and the male is more likely to drive the car with the most safety features and the bigger car. So the male not only has a car which is designed to keep him safe, but also has the most modern safety features. So the male is more likely to drive the car to drive as well, whereas the female tends to get the older, less safe vehicle and none of these cars have been designed around protecting females.

So there’s many, many issues there, some of which I’ve just touched upon, both in terms of biological characteristics, the characteristics of the accidents that we have, but very importantly, how cars are designed and how cars are designed around the male norm, rather than the female norm.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

Oh, wow. You know, this is, this is all very, very shocking. Because you spoke about the fact that it was just recently started trying car safety with female mannequins. And it’s crazy because, so do they mean that women do not get into the cars?

Like why do not make, why they do not make provision for the safety of women? It’s, I don’t know. It’s shocking. It’s shocking to me. Like, why would they do that? And women make up,

make up almost half of the population of the world, like 49 point something percent. And they’re designing cars without putting these people in mind. It’s just baffling.

It really is baffling.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

I think there is misogyny almost everywhere. (Yes, actually.) I say that because when you were talking, when you were talking about the car design, I was like, okay, is it, do we call it car industry sexism, or automotive misogyny? And I say that because I’m Muslim. And sometimes when you go to some place of worship, you see smaller spaces for women and bigger spaces for men. And I call it architectural misogyny because when they are smaller spaces, it does not allow so many women to be in a place of worship. That way we miss out on the spirituality of worshiping in a mosque. But we have larger spaces for men.

So you can have 1000 men and maybe like what, 10 women. That’s not fair. So where should, where should the rest of the women be? It’s not fair.

No one should have to miss out on being able to worship where they feel very spiritual and all of that. So, and this links to the car industry as well. They are designing cars mainly, (mainly for men), mainly for men.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: It’s so, it’s, I don’t know. It’s actually really, it’s shocking. I’ll keep saying it’s shocking because you know, like I know that when, when there are accidents, we see that women tend to suffer more. They get to have more serious injuries than men. So honestly, I had no idea that it was because of the design that it was mostly designed for men.

So thank you for sharing this with us. Thank you for sharing it and for doing the research. It’s, it’s eye opening to be honest.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba: You know, it’s funny because my next question had to do with medical misogyny.

And I, I mean, we were, were, we were short of words because you experience medical misogyny all the time. So what advice would you give?

What advice would you give in navigating this challenging situation in the medical field?

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

What advice would I give as a patient or what advice would I give as a healthcare worker looking to challenge it?

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: Well, both.

Dr Tim Nutbeam:

Both. Okay. I think we’ve discussed some of the—how do you challenge misogyny in your workplace? We’ve talked about leadership role models. We’ve talked about policies and procedures. We’ve talked about supportive cultures.

We’ve talked about calling it out when it occurs. We’ve talked about the importance of education and, and kind of dealing with everything from microaggressions all the way through to, you know, HR type,

type issues as well. I think as a patient, it’s a real challenge and I don’t have much experience from the other side from seeing it from a patient’s perspective.

But I think we all need to be aware of these issues and try to educate ourselves around these issues. And then when we see them, we need to feel empowered to challenge them. And I know that’s incredibly difficult, particularly with often this power gradient between a clinical health provider, be it a nurse or a doctor, and you as a patient.

But often, you know, once these issues are raised, and once a healthy kind of balanced, psychologically safe discussion occurs, then a way forward can be found, but there is something around education.

There is something around accepting that we’ve got a problem. And there is something around empowering our patients to ask.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:

I have a question and I, this is very personal. This is very personal. We cannot talk about trauma, collision, accidents without talking about pregnant women and in conversations with our peers, when we have this conversation, because, you know, it’s easy to say, “oh, this will never happen to me, God forbid”. But like, you know what, what if these things happen? And I hear answers.

And I’d like to ask you personally, I know you see lots of pregnant women who would have been brought to the emergency. And you, you know, that conversation around mother or unborn baby. We hear so many people amongst us fight so strongly.

And they say that, “oh, they would rather save their unborn baby over their wives”. And because we are women, we have conversations like, again, you can, you probably might, if you mind for companionship, it means that you want to have your partner for the rest of your life or to do your part or whatever does your part. You know, you can have another baby. Why do you aggressively fight to save your child’s life when you should be saving your other half’s life?

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

No, but the thing is, they don’t get to make that decision. It’s just a Twitter conversation. Right?

Rihanot Ojo-Oba: Oh, do they? Oh, they don’t?

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi:

They don’t get to make that decision. It’s just a Twitter conversation.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba: I thought it was a doctor asking the partner, do you want us to save the mother or the baby or?

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: Doctors have come to debunk it, that the doctors would make the decision.

Right, Dr. Tim?

Dr Tim Nutbeam: So the ethical framework here is if you look after the mother, then you’ll save the baby. We very very rarely or never have to make a decision between saving the mum and saving the child.

Very occasionally, there’s an issue where perhaps the woman has been very very majorly injured and would otherwise die and we can keep her alive using intensive care and those sort of things until the baby is safe to deliver, but that woman would’ve died regardless.

We’re just kind of extending that process so the baby can be delivered safely. Our ethical framework is very clear; you look after the mum and by looking after the mum, you protect the child.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: So following your findings on gender differences in collision outcomes, how do you think we can address these disparities and reduce them to the barest minimum?

Dr Tim Nutbeam: In more recent years, we have seen cars which have been more equitably tested for males and for females and are safe both for males and females.

Ideally, we would use the purchasing power of the market to invest in those vehicles and for people to realize—for those who manufacture cars to realize how important it is to the population.

So I know that some really good work happened in other areas of the world where they’ve enabled, they’ve educated car purchases around what’s important when choosing a car and as a result, gave encouraged manufacturers to make safety systems more universally available and also at a lower price.

Cause often particularly for certain markets, Manufacturers have producing the cheapest car possible rather than the best car possible. And it’s only by consumer pressure that we can make these things change.

Of course, there is a role for legislation and it be fantastic if the United Nations and other groups which set car manufacturer standards make sure that cars were tested equitably and tested equitably for all markets, not just the premium market or for the higher income country market.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: Alright, thank you for this conversation. We have been able to shed light on a couple of structural misogyny, and also find ways to address it.

So what final words would you leave with our listeners before we let you go?

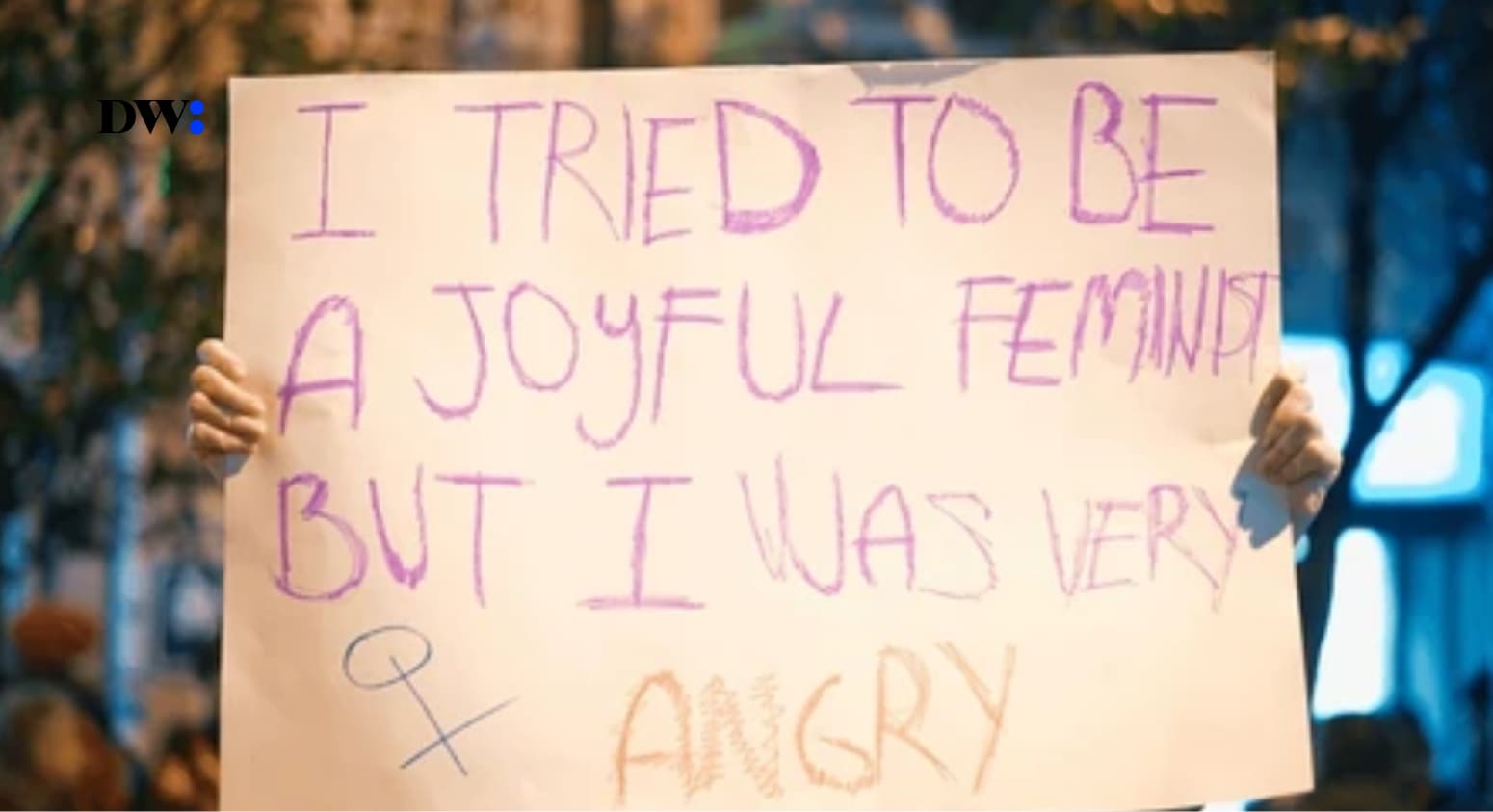

Dr Tim Nutbeam: I think many people still struggle to accept that our world has been crafted around the white male norm and I think it is really difficult to move forward and address some of these inequities until we get those people on board and sometimes those conversations are really challenging and sometimes that’s really difficult.

But actually, bringing everyone along on this journey is a really important part of success so for those of you promoting this work like yourselves, thank you. I think we’re making small steps in the right direction.

I’d encourage your listeners to continue challenging inequities when they see it, but also trying to bring people along on the journey with them so they can understand some of these issues. Whether it be for education or whether it be through no modelling of great behaviours.

Tiaraoluwa Fadeyi: Thank you for sharing your expertise with us and for the work you’re doing, you’ve doing amazing and the work you’re doing on medical misogyny is truly inspiring.

So thank you very much.

Rihanot Ojo-Oba:Thank you to our listeners. We hope that this episode has shed light on an important aspect of women’s health care and the challenges within the medical profession.

Read and Listen to all other episodes of The Counter Narrative podcast for more enlightening discussions.