Many people love Chimamanda Adichie’s seminal TedTalk titled We Should All Be Feminists. For some people, it was her explaining sexist concepts using easy-to-understand language. For others, it was her using examples relatable to African women to illustrate the dangers of sexism.

When I think of Adichie’s Tedtalk, one quote sticks in my mind. In talking about the belief that political power was for men alone, Ms Adichie quoted the late Kenyan environmental activist Wangari Maathai.

“The late Kenyan Nobel laureate put it well when she said: ‘The higher you go, the fewer women there are”, Chimamanda said.

I think of this quote each time a political season kicks off in Nigeria, and it is almost expected that those running for president will be men.

When I think of how it is primarily men who are landowners, landlords and property owners in Lagos and other cities, that quote reverberates in my mind.

Do girls and young women conceptualize politics? How do they view their political leaders and do they feel properly represented within the political sphere?

The Independent National Electoral Commission released an official list of candidates vying for political positions in the upcoming 2023 Elections. Out of the 4,256 names in that document, only 381 women are listed as those running for president and seats in the federal parliament.

The national average of women’s political participation in Nigeria stands at 6.7 per cent in elective and appointive positions, according to data from Gender Strategy Advancement International. This is far below the global average of 22.5 per cent, Africa’s regional average of 23.4 per cent and the West African Sub Regional Average of 15 per cent.

The World Gender Gap report 2022 reveals that Nigeria ranks 123rd with a score of 0.639 out of 146 countries. The ranking on gender gap parity uses parameters like economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, political appointment and financial exclusion/wealth accumulation of the female gender in the world.

There’s also the issue of women’s political representation in the military as well. I do not like the police and the military. I understand that they were created to serve practical and needed desires in any community, but I do not like them. They remind me of violence and a deep devotion to causing harm and trauma.

I once remember coming back from school, and in traffic, I watched an army officer beat up drivers who he felt were causing the stall in movement. The historic anti-police brutality #EndSARS protests that were held this month two years ago do nothing but reaffirm my stance.

As much as I do not like the armed forces, I have fond memories growing up around army and police women who showed me the power of representation and women being active in every sphere of society. At Church, women in the military spoke passively of dismantling an AK-47 in one breath, and the next breath, were involved in caring for their children.

One such woman stood out for me. She was a single mother known in the entire church as being very outspoken. Unusually, she was never given the heat from having a daughter outside of marriage and was often involved in church activities. Her presence drew respect even from those who felt that they had toed more respectable backgrounds. Her daughter, too, was not afraid and, from a young age, spoke her mind knowing that she had a confidante in her mother.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dear Ijeawele, she asked her readers to question why power is seen as an aberration for women. She asked her readers to examine why women in power had to wear their power lightly in a manner that could only bring to mind a performance of incredible shapeshifting.

In the news, we see women who are politicians being questioned endlessly about their maternal and wifely sides. A woman aspiring to a political role must emphasise how she is the one in complete control of her domestic duties at home in addition to her public duties.

In the series King of Boys. Eniola Salami, a political aspirant, was advised by her PR Team to leak to the Nigerian media that she was engaged to be married. Salami, a widow, said she had no plans of remarrying. She herself eventually got the political seat not from wiggling and dancing to the tunes of sexism but from utilising the power and fear that came with her name.

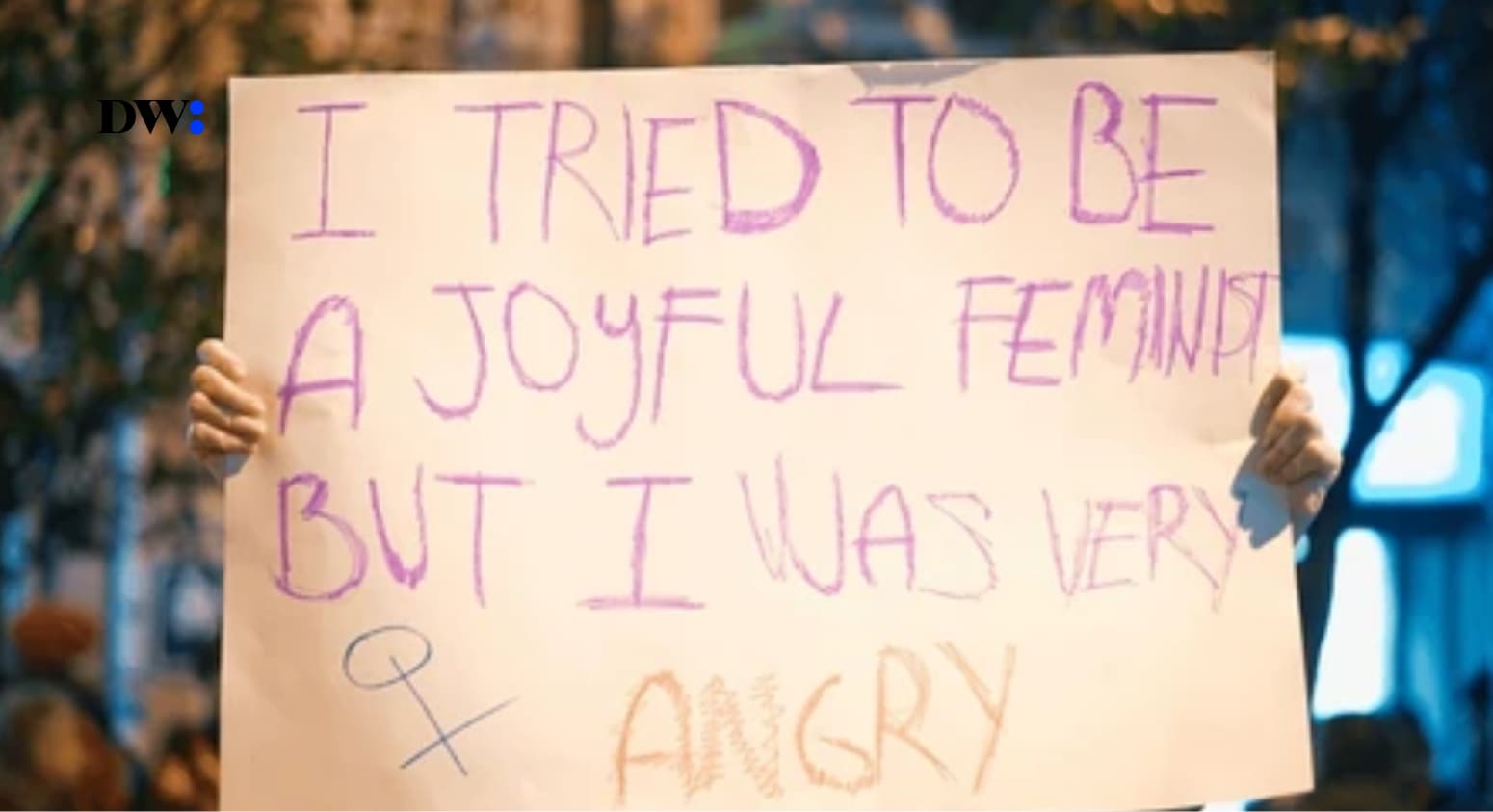

One of my firm beliefs as a journalist is documenting women who veer away from what is deemed respectable in the eyes of society. I’m interested in telling the stories of women who are bold enough to break the mold and to seek power shamelessly. I genuinely believe that one thing that shapes a young girl’s ability to have confidence in any given field is the possibility of her growing up seeing women in those fields.

Women like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie stand in the truth that speaking for women is not invalid. Before her, Buchi Emecheta gave me the audacity to call out abhorrent Igbo customs without worrying if I was less of an Igbo woman.

In the public space, it is also imperative that young girls grow up witnessing women partake in the areas that command respect and authority.

Decision makers at all levels must institutionalise the meaningful and safe participation of women and their groups through the adoption of fully resourced and accountable policies, strategies and frameworks.

Both state and non state actors should recognise women’s role in civil society and provide accessible resources so that girls’ organisations are sustainable in the face of crises and external threats.